“Jazz has endured because it doesn’t have a beginning or an ending. It’s a moment.” – Robert Altman.

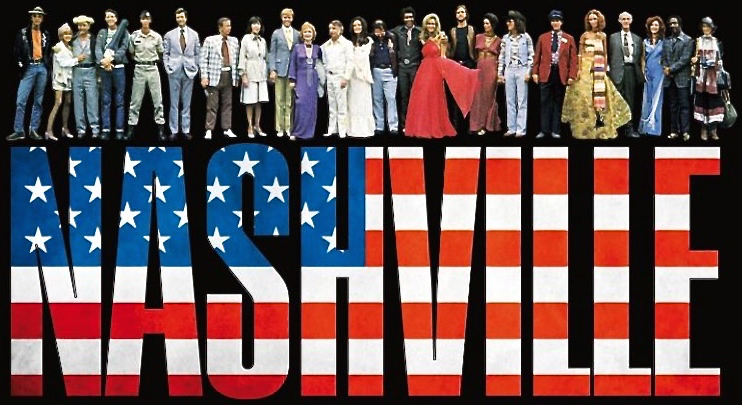

Some of my favorite films are ‘mosaics’. A fistful of the best include Nashville (1975), MASH (1970), The Player (1992) and Short Cuts (1993). Made by American movie pioneer, Robert Altman (1925 – 2006), they’re shining examples of supremely satisfying, subversive cinematic storytelling, as intricately constructed as a Mesopotamian temple.

And so it goes: the paths of a multitude of seemingly discreet characters intersect and intertwine, eventually moving together as one towards a powerful denouement. Sounds like jazz to me.

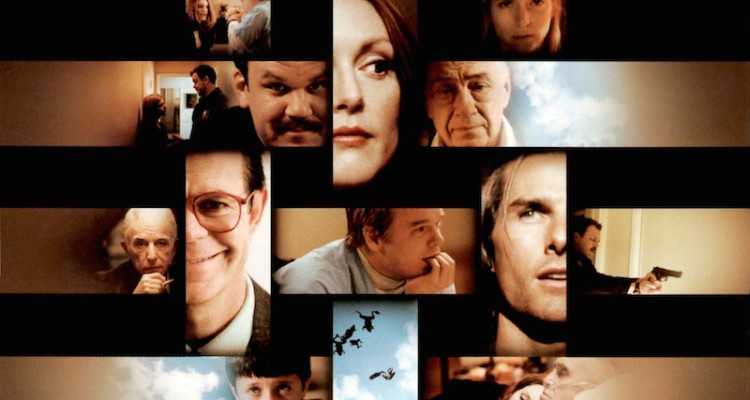

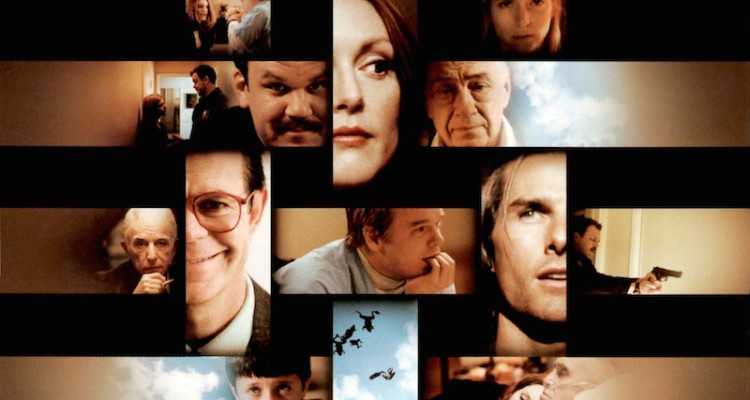

Paul Thomas Anderson’s epic, sprawling tragedy Magnolia (1999) is another tapestry with a baker’s dozen worth of characters – and story lines – effortlessly held in the air all at once. As is Australian classic Lantana (2001), written by Andrew Bovell and directed by Ray Lawrence. A film I hold close to my heart, it’s a deeply affecting, serpentine, slow-burn of a ‘whodunnit’ filled with flawed characters who are somehow redeemed, dragged backwards through the thorny bushes of Australian suburbia.

Soon another mosaic will unfurl it’s multi-narrative feature tendrils. Kriv Stenders’ drama Australia Day (2017) will have its home entertainment release in January, telling three overlapping stories about racism and redemption in ‘real time’. Just in time for “Straya Day”, our most contentious of (colonial) public holidays.

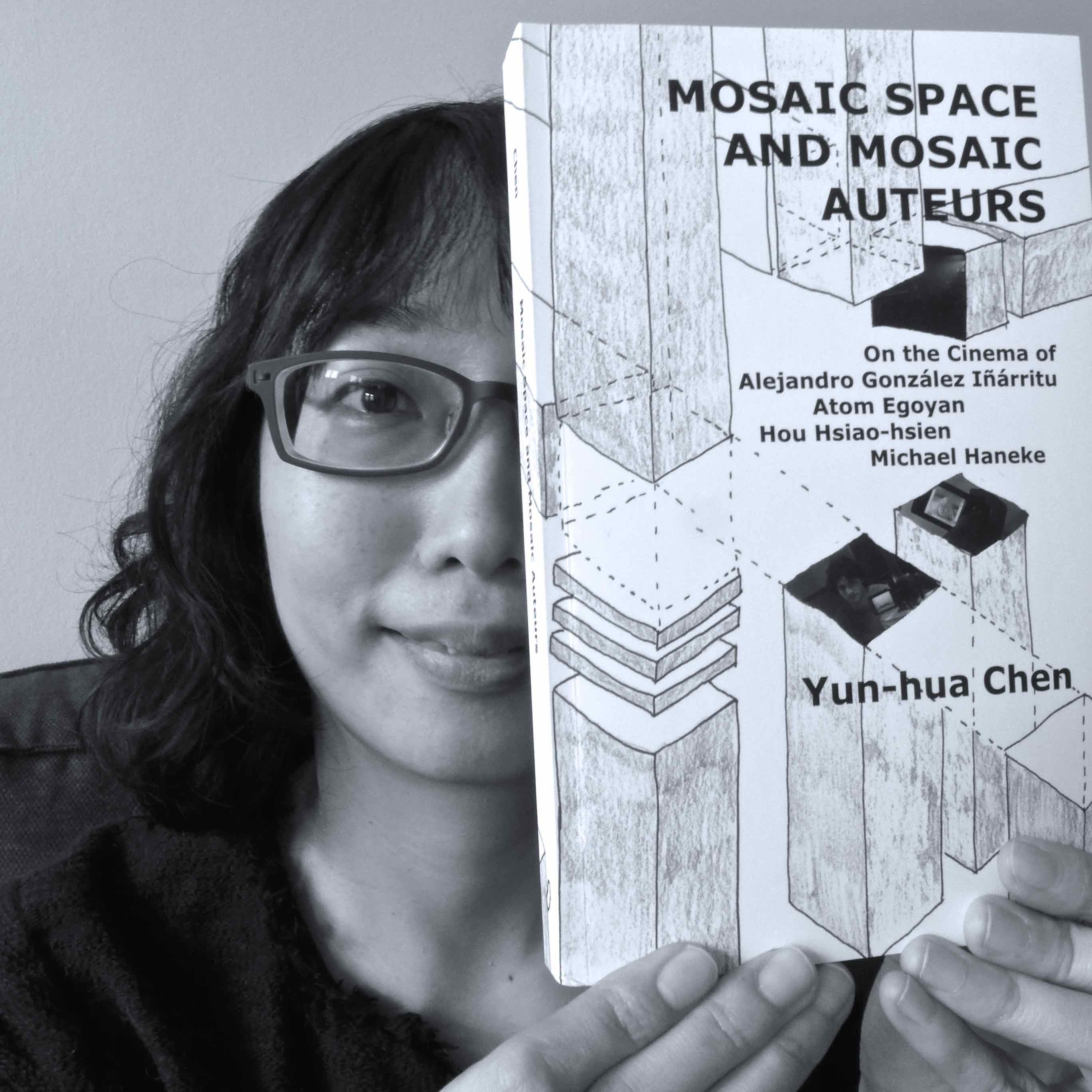

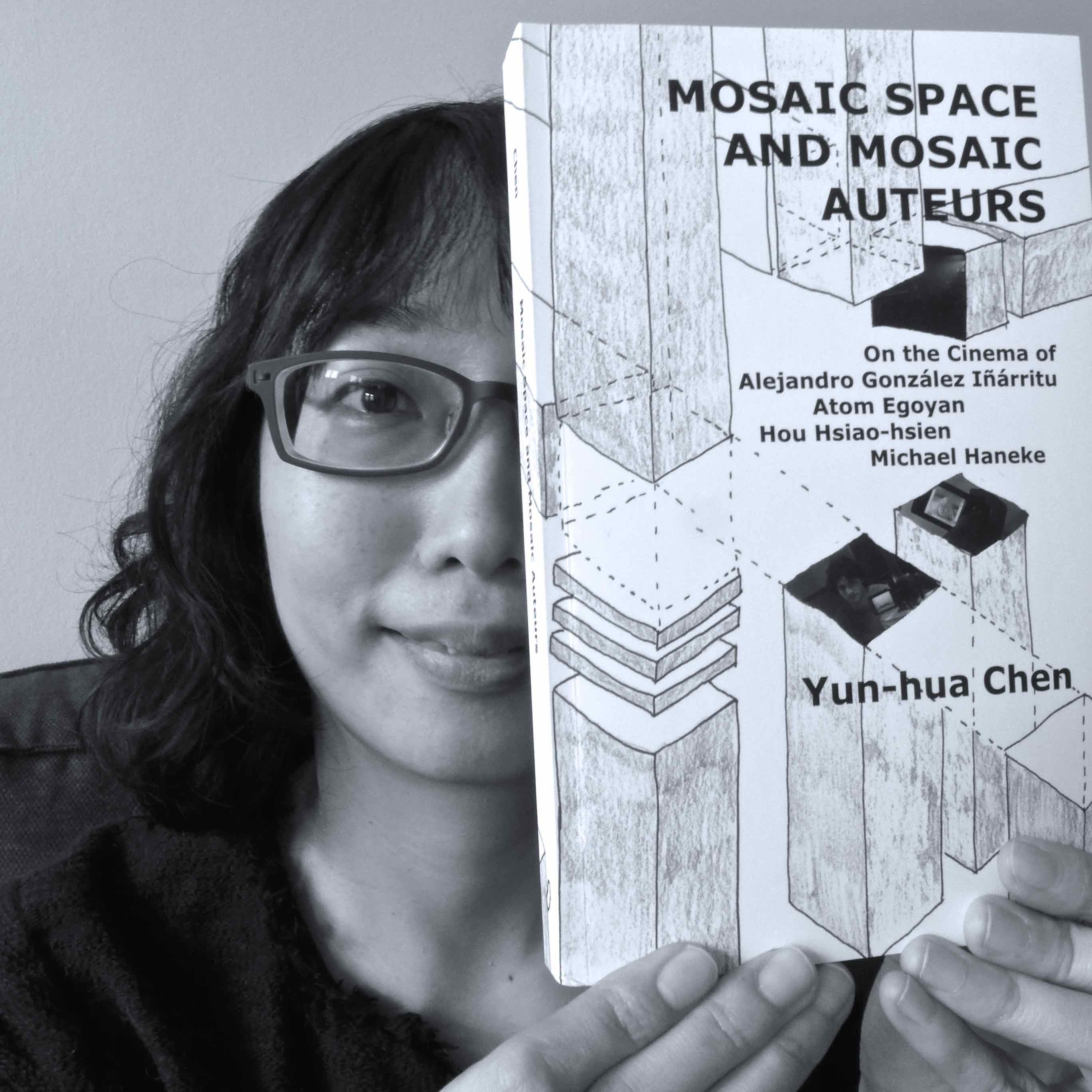

Mosaic filmmaking – aka “circular” or “multi-protagonist” narrative – requires not only a certain way of seeing life and how we live it, but the potential of the film medium itself. That’s the contention of film critic, author, linguist and academic, Yun-hua Chen.

Taiwanese-born and Berlin-based, she’s written book ‘Mosaic Space and Mosaic Auteurs’ (2017), a 258-page treatise on this ambitious, imaginative film style, which she says harks back to the days of silent cinema with D.W. Griffiths’ groundbreaking Intolerance (1916). “His films are some of the very first which consciously construct a mosaic narrative through editing, with a very clear purpose in mind,” she asserts.

Still from Hou Hsiao-hsien’s ‘A City Of Sadness’ (1989).

Focusing on four of the world’s leading proponents of mosaic cinema – Alejandro González Iñárritu (Mexico), Atom Egoyan (Canada), Hou Hsiao-hsien (Taiwan) and Michael Haneke (Austria) – in expert detail Yun-hua explores their work and techniques within the broader context of the shifting sands of our transnational, non-binary, “post-truth” globalized world.

When you think about it, her timing is perfect…

It’s an engrossing and compelling read, positing fascinating theories around time, space, place, identity and – as Altman might have it – the cinematic “moment”. And, how these elements are brandished within each filmmaker’s oeuvre.

At a chance moment of our own Yun-hua and I met at the 2017 Berlinale. Working as critics we saw 100 films together, formed a tiny film posse, ate Japanese food in the dark, made a podcast about the experience and riffed on film until the cows came home.

When I discovered she’d written a book about mosaic film, I couldn’t wait to hear more. So we decided to share another movie moment here on Circus Folk…

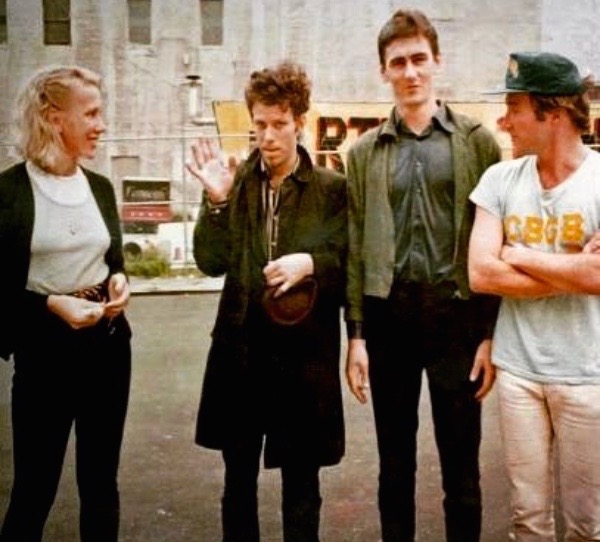

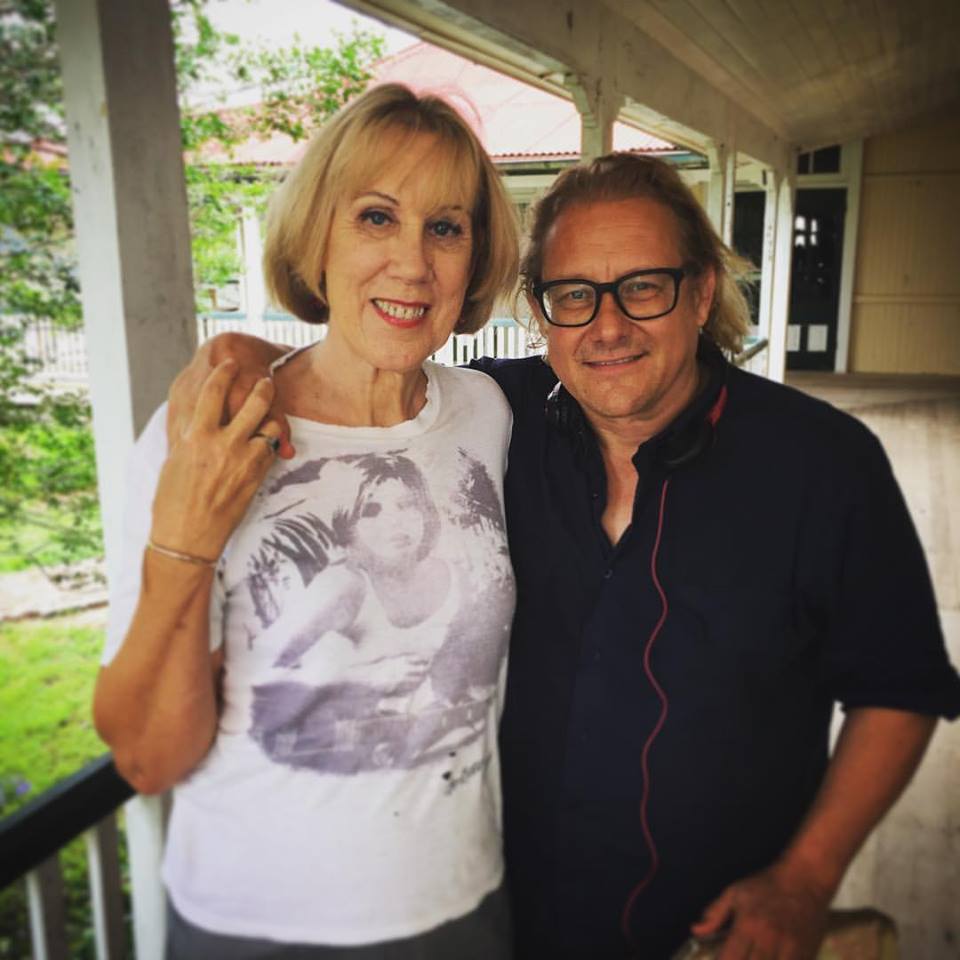

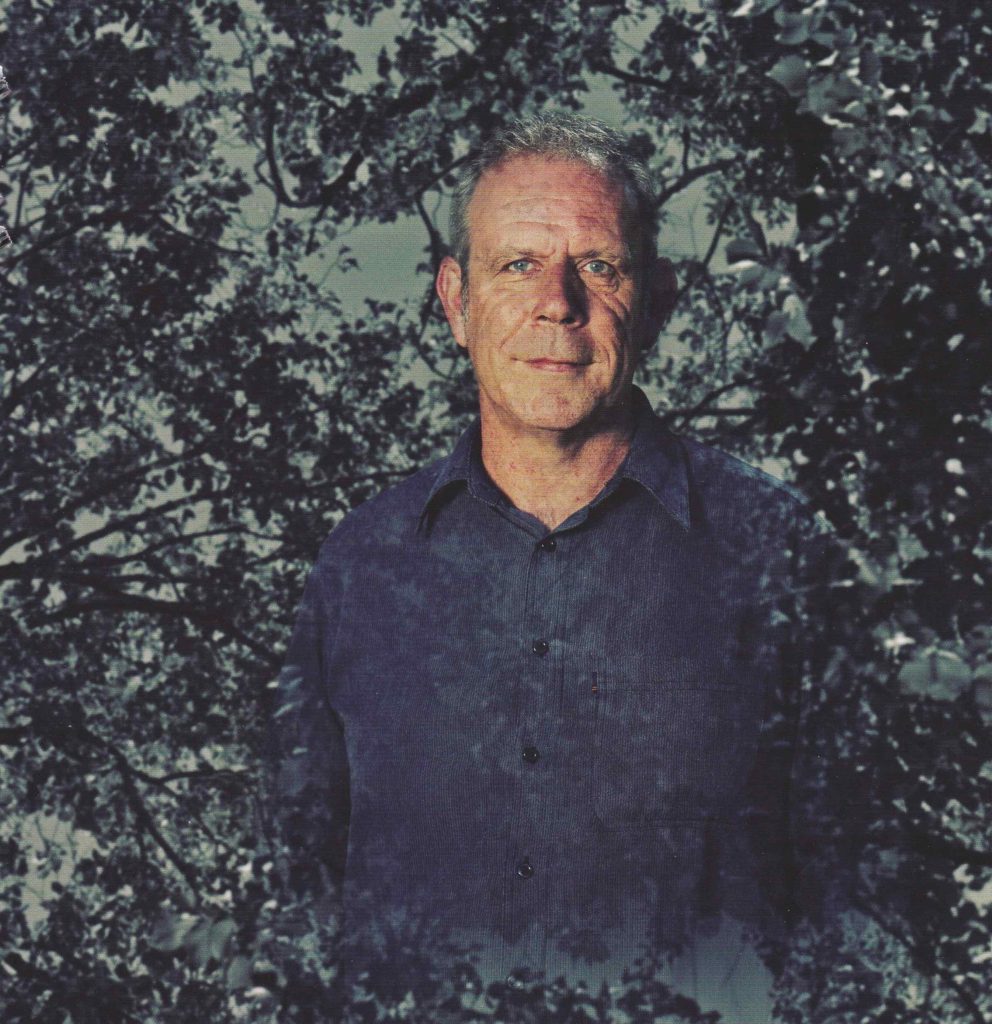

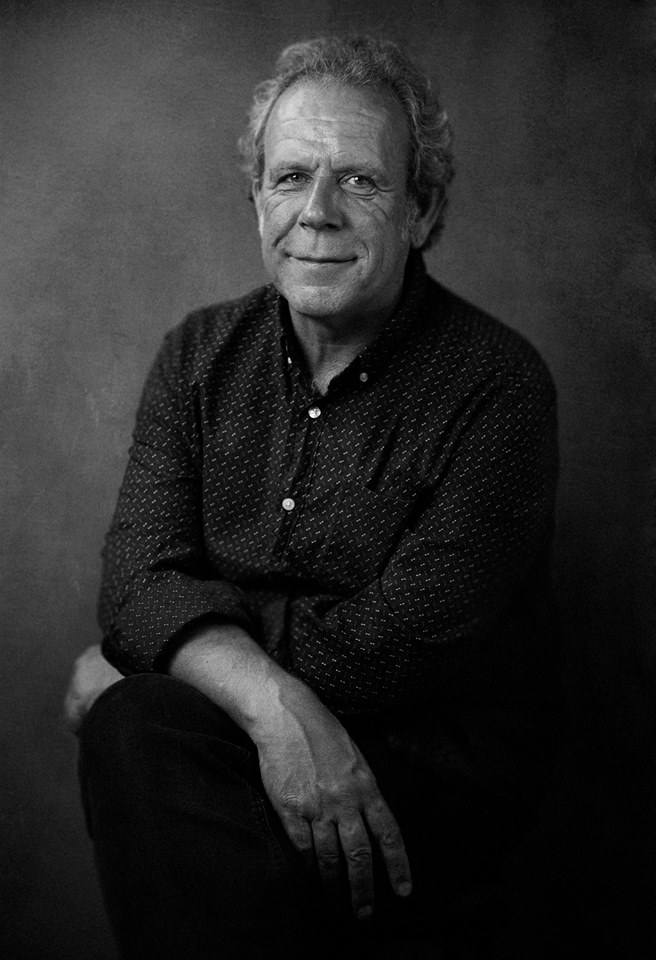

Yun-hua Chen in Berlin. Photo: Megan Spencer (c) 2017

Circus Folk: Let’s start with the late Robert Altman: when it comes to multi-protagonist, inter-woven narrative film I always think of his films and how incredibly satisfying they are, even when the storylines are left a bit open-ended and not all tied up in a neat bow (Nashville in particular.)

Who are some of the mosaic film pioneers? And perhaps some of those that have been most influential on you?

Yun-hua Chen: I agree: Robert Altman is one of my favorite filmmakers who churned out inspiring mosaic films.

For other pioneers I would name the filmmakers as far back as D. W. Griffith’s Intolerance (1916) and Jean-Luc Godard’s polemical works in the 1960s.

The most influential ones for me personally are the mosaic films which are more labyrinthine and puzzling such as Alain Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad (1961) and David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive (2001) and Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s films including Tropical Malady (2004), Syndromes and A Century (2006) and Cemetery of Splendor (2015).

I really enjoy mosaic films that deliberately break down our expectations of linearity and any kind of logical connection. My recent favorites are Kaili Blues (2015) of Bi Gan and Ghost in the Mountains (2017) of Heng Yang. And, En Attendant les Hirondelles (2017) which I watched with great joy at the Viennale International film Festival this year.

CF: What was the first mosaic film you ever saw?

YhC: If we take a very loose definition of “mosaic”, the first I ever saw was L’Appartement (1996, Gilles Mimouni), which screened at a French Film Festival in Taiwan at that time. I was fascinated by the clever maneuvering of the narrative threads; the suspense – which was maintained throughout the film – and trompe l’oeil [optical illusion or “forced perspective”] in terms of the characters and timelines.

So I think my interest in how our presumptions and perceptions can be manipulated by film through a visual and audial manner stemmed from seeing it.

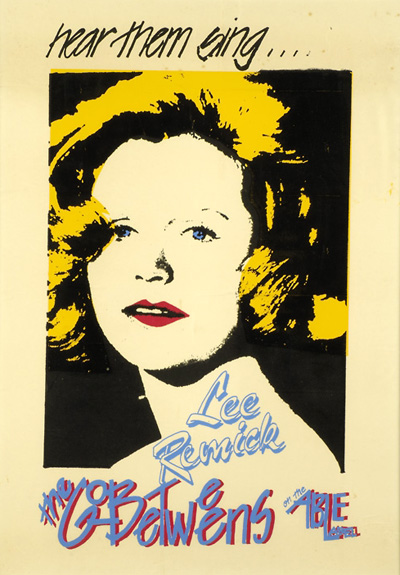

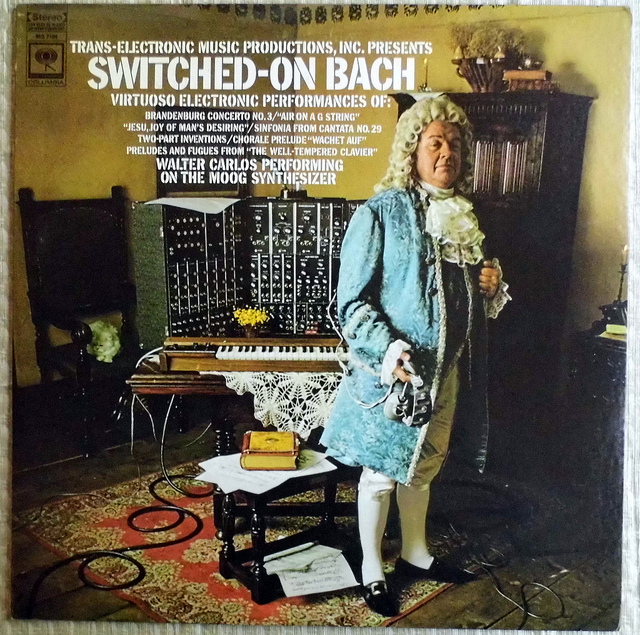

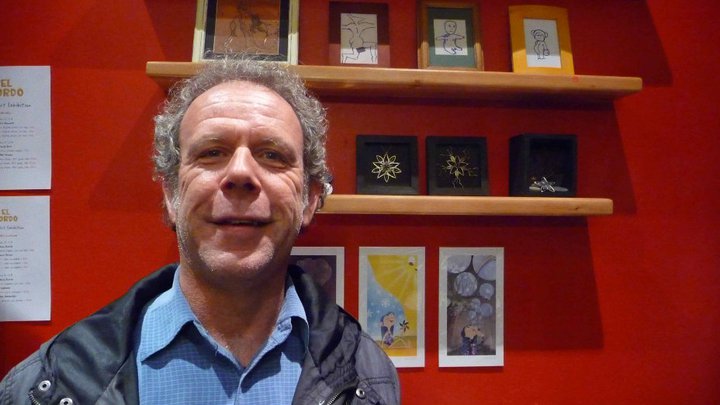

‘Nashville’ soundtrack album cover art, directed by Robert Altman, 1975.

CF: I usually think of music as the most ‘immediate’ mosaic space in the arts: a space where it is accepted, the norm and quite feasible for unique, seemingly discreet or oblique elements and styles to intertwine to make a ‘whole’ piece that works perfectly well as the sum of its parts. In film though, this kind of narrative ‘tapestry’ is more of a rarity; it’s usually much more conservative and linear.

Why might that be so?

YhC: It might have something to do with the way we understand narratives in a visual way, and the way we consume different art forms in different manners.

From Soviet montage we learned a lot [as it] extensively experimented with juxtaposition between oppositional images. Since then narrative experimentation still goes on – and continues to flourish – but it is rather restricted to a particular field with a particular ‘set’ of audiences.

Compared to [the] more easily consumable ‘linear narrative’, although it still offers pleasure and satisfaction, narrative “tapestry” [or “mosaics”] might find it more difficult to appeal to a wider audience and on a greater scale.

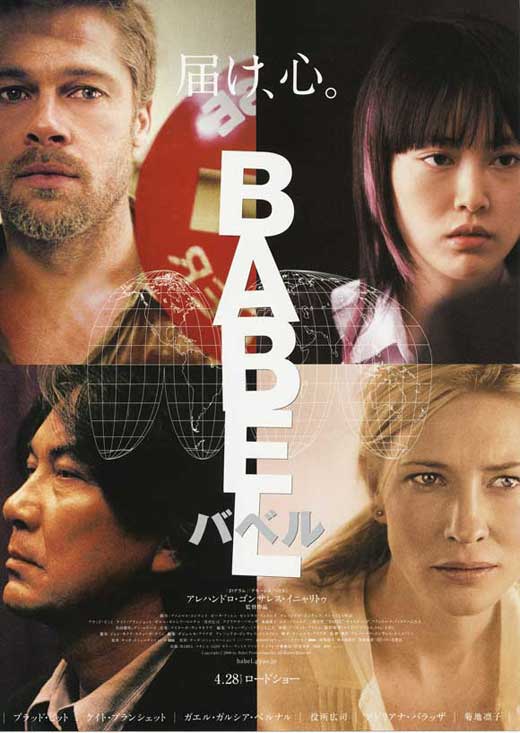

After the 90s outburst of ‘multi-protagonist’ films, [until] Babel (2006), the multi-protagonist film was exhausted, starting to seem unsexy and archaic. However with the advances of interactive virtual reality, there might be new opportunities to revolutionize the “mosaic” narrative form.

Film poster for Alejandro González Iñárritu’s ‘Babel’, 2006.

CF: Given mosaic films are more complicated to conceive of and make (and likely more expensive too – thinking of Iñárritu’s Babel for one, shot across three continents with a myriad of stars and actors): why would you bother?!

What usually attracts a filmmaker to making a “mosaic”, rather than a film with more straightforward, linear structure? What kind of filmmaker do you need to be to undertake such a project?

YhC: It could take a certain way of thinking and looking at the world that drives some filmmakers to mosaic filmmaking – like the devoted Mexican director, screenwriter, author Guillermo Arriaga who is also renowned also for “mosaic narrative” in his novels…

Or a stylistic choice as in the case of Alejandro González Iñárritu (21 Grams, Babel) who was an experienced MTV director and interested in experimenting with narrative form within commercial [feature] filmmaking.

You [do] need to be a filmmaker who is genuinely interested in editing and very talented in seeing fragments in a holistic manner to be able to undertake such a project. And have a particular worldview and an understanding of the inherent fragmentation, discontinuity and disjointedness [in life].

I think making mosaic films can be addictive: Hong Kong director Wong Kar-Wei has never made a film without a strong mosaic element in it. And Iñárritu still keeps his signature of mosaic even while attempting to go to the other extreme, by making seemingly one-shot films like Birdman (2014) and The Revenant (2015).

What attracts filmmakers to making a mosaic should be their inner drive of telling a certain story in a certain manner. I think the most apparent example is the aforementioned Arriaga, the long-term scriptwriter of Iñárritu’s films (until the rupture*). He is someone with a very strong drive of mosaic; his novels are mosaic and he thinks like a mosaic.

*Arriaga and Iñárritu reportedly had a disagreement over credit for ‘Babel’, leading the former to be banned from the Cannes premiere by the latter.

After his fallout with Iñárritu, he made a debut film The Burning Plain (2008) – by the way, a total disaster in many ways! But it seems that mosaic is his existential question and obsession.

However Austrian director Michael Haneke [who I also write about in the book], doesn’t have the same kind of mosaic ‘drive’. Instead he uses mosaic as a means to reach his goal of foregrounding contemporary society, and our mode of consumption of media.

So whereas mosaic is a drive – even a curse sometimes – for artists such as Arriaga and Iñárritu who have not yet managed to completely depart from it – for others, mosaic is an aesthetic tool out of pragmatic concerns.

Some artists look at the world in an ‘impressionist’ way and some look at it in a ‘mosaic’ way. The latter see assemblages rather than continuity, asynchronity rather than linearity.

I feel that to a certain extent this might also be the way I see the world, and that’s also why writing ‘Mosaic Spaces And Mosaic Auteurs’ was so attractive to me.

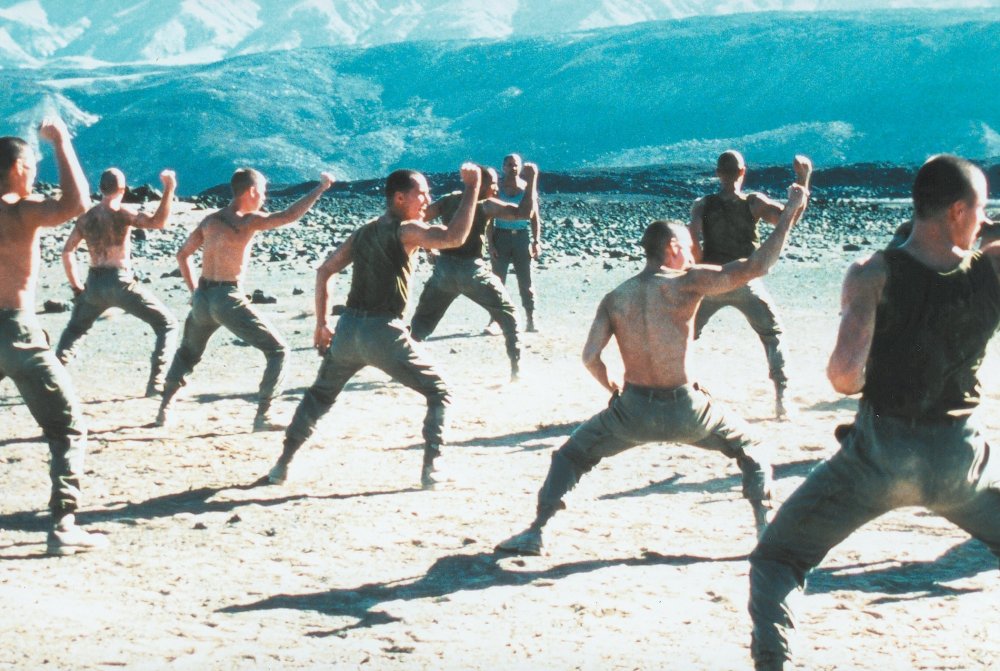

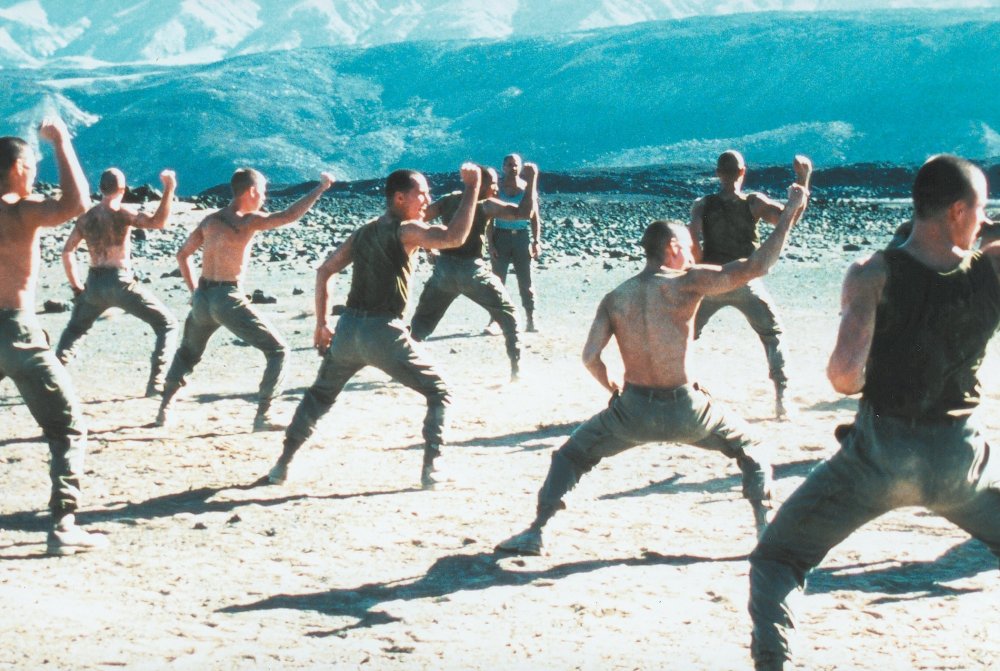

Film still from Claire Denis’ 1999 feature, ‘Beau Travail’.

CF: Because I often find mosaic cinema narratives really powerful, I get really irked when I see a “bad” one – those films that use the style more as a gimmick, a cynical ”trick” or a quirk to lure the audience into a narrative rather than explore something artfully by using this powerful style – style over substance so to speak! (Snatch and Love Actually come to mind)

What makes a ‘good’ mosaic film? And do you have examples of ‘bad’ ones?

YhC: Yes – I have a lot of examples of “bad” ones, ha ha! For me, “bad” ones are either as you said – [use mosaic as] a gimmick or a “trick” rather than something substantial. Or they are simply boring [where use of the style is] unnecessary.

Arriaga comes to mind again. As much as he uses mosaic in a powerful way through language, his mosaic through visual and audial means in The Burning Plain is far from being successful – totally agreeing with your criticism of “style over substance”!

This can tell us a lot about how film works as a unique art form which goes beyond just telling a good story: I think good mosaic films use different cinematic elements in a clever way to bring out something new, weaving something that has never been done before.

For me one important factor for the good ones would be a ‘mosaic beyond mosaic’ narrative, meaning a mosaic that is an interweaving of mosaic narrative, sound elements, different parts of the mise-en-scene (like what Chinese filmmaker Hou Hsiao-hsien does in his films), and much more.

Good mosaic films also have a balanced approach to content and form without skewing over to the ‘style’ side. I think good mosaic films are not carried away by the inner drive towards fragmentation but rather keep a clear head about what is important in this visual and audial product. [They draw a clear line between] what is inspiring and what is purely ‘showing off’.

Film still from Atom Egoyan’s 1997 film, ‘The Sweet Hereafter’.

Film still from Michael Haneke’s ‘Caché’ (“Hidden”, 2005).

Film still from Ray Lawrence’s ‘Lantana’ (2002).

Spaces & places: Yun-hua Chen. Photo: Megan Spencer (c) 2017

CF: The four mosaic auteurs you chose for your book were motivated by particular decisions: what were they? And what types of mosaics do you discuss in your book?

YhC: The foremost decision driver for the choice of these four mosaic auteurs was global scope. As one of the main aims of talking about mosaic auteurs was to talk about a way of looking at cinema that crosses boundaries – one that demonstrates an innate mutually-feeding and -influencing network between diegetic cinematic elements and extradiegetic filmmaking contexts – it was very important for me to choose mosaic auteurs who could demonstrate these global networks and border-crossing/boundary-crossing phenomena.

Another was to do this by coming from a perspective that intentionally and innately avoids Euro-centrism.

For these reasons I included Michael Haneke, whose filmmaking networks are mainly based in Europe but also branch out to the US with the American remake of Funny Games (2007) which he also directed. [The film was originally made by Haneke in Austria in 1997].

Also Alejandro Gonzalez Iñárritu who mainly works in the continent of America but also consciously maps out to the global arena especially through ambitious mosaic projects such as Babel.

Hou Hsiao-hsien who works in the context of Asia and is strongly connected with the French funding system and cinephilia culture, and Atom Egoyan who works mainly in Canada and Armenia – as an attempt to achieve some sort of a balance between the continents of Asia, Europe and America.

Sadly I was not able to include Australia and Africa. I do think that they should have been included as there are a lot of mosaics to be written about in the cinemas of Australia and Africa. (What comes to my mind immediately is Jane Campion’s films and TV productions such as Top of the Lake (2013 – 2017), and Abderrahmane Sissako’s films including Timbuktu (2014).) This would have to be another book project!

[Regarding the kinds of mosaics I explore in the book though] – at the beginning of the 21st century there were a lot of films that portrayed multiple narratives: network narratives, multi-character narratives. One of the most famous filmmakers who made these kinds of films was Iñárritu with Amores Perros, 21 Grams and Babel. These films spread out across different geographical spaces, especially in Babel. That is a horizontal mosaic, assembled from different social milieus, socio-political backgrounds and contexts, but in a specific time.

When a strong element of history is brought in, like in the films of Atom Egoyan and Hou Hsiao-hsen, time becomes an important factor in itself. That is a vertical mosaic: one that deals with history.

When vertical and horizontal axes intersect, a three-dimensional mosaic emerges. Michael Haneke for example interweaves different socio-political spaces and milieus, while at the same time being concerned with understanding the impact of historical events and ‘the virtual’.

So my book is structured in this fashion: we move from horizontal mosaic to vertical mosaic, and then end with three-dimensional mosaic, which combines both.

I think making mosaic films can be addictive… What attracts filmmakers to making a mosaic should be their inner drive of telling a certain story in a certain manner.

CF: Why is the mosaic structure useful within the film context? What kinds of conversations can a mosaic have with an audience that other kinds of films cannot?

YhC: Mosaic structure is useful in many aspects, for its ability to connect and interconnect, its balance between fragmentation and assemblage, and its boundary-crossing capacity.

At the peak of mosaic filmmaking (in the 1990s), these films communicated the global interconnected-ness that everyone was experiencing, and the juxtaposition between different spatial concepts, like ‘the local’ and ‘the global’, places and ‘non-places’, the smooth and the striated – all which I discussed in the book.

When we watched Babel we all understood that, regardless of where we are, where we are from, how we live, and what we believe in, we have an impact on one another even in a very distant and sometimes invisible manner. At the same time there are forces that we cannot see which might originate from a place distant to our immediate proximity, that strongly influence our lives.

Film poster for P.T. Anderson’s ‘Magnolia’ (1999).

For the sake of convenience, if I may use the terms “global” and “globalization” in a very rudimentary and generalized manner here – this sense of being connected on a global scale and embracing globalization as well as all that comes with it – has been challenged since the financial crisis was triggered by Lehman Brothers in 2007.

I would argue that the fact that there are less mosaic films being produced and appreciated since that time is related to the feelings of resentment for the negative effects of global interconnected-ness, and the reflections on it, which, to a large extent, have returned us to our local and the immediate surroundings.

So mosaic, as a result of the filmmakers’ reflections through their films – and reach through their distribution networks around the world – in turn reflects the zeitgeist and the way the audience might feel about life, and ‘the times’. I think this kind of mutually feeding conversation between mosaic films and the audience is fruitful and very interesting. It goes into a reflexive loop.

CF: Did you do any research on the affect a mosaic film has on an audience? Are they more satisfying to watch, for example?

YhC: This would be a very interesting topic to look at for sure. For this specific project I didn’t do any empirical study on spectatorship. But the box office returns on these kinds of films do diverge quite a lot [which] at a guess [may be an indicator].

For example, Iñárritu’s Amores Perros, 21 Grams, and Babel were hugely successful in terms of box office on a global scale. And Hou Hsiao-hsien‘s A City of Sadness was a record-breaker – until 2007 the largest grossing film in Taiwan.

But at the same time [again going by box office] Atom Egoyan’s Exotica, Family Viewing, Adjuster and Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Good Men, Good Women, Inarritu’s Biutiful and Haneke’s Time of the Wolf did not seem that attractive to audiences.

In terms of ‘satisfaction’, I think that the sense of satisfaction an audience feels during a mosaic film might have something to do with a sense of resolution: the coming-together of all the narrative threads, like solving a puzzle or cracking a detective game.

However in the case of the mosaics of Hou Hsiao-hsien, Michael Haneke and Atom Egoyan, in fact more puzzles are added instead of solved in the viewing experience. So the classical sense of ‘satisfaction’ is probably replaced by some other satisfaction on a more ‘intellectual’ level, and hence the appeal perhaps is to a smaller pool of the audience.

It also has to do with the timing of the release: Hou’s A City of Sadness (1989) came out right after the lifting of Martial Law in Taiwan in 1987, and speaks directly to the audience who experienced that [38-year] history together, but were previously forbidden to discuss the trauma.

Iñárritu’s first few films came out at the perfect time to speak to the MTV generation who craved an aesthetic closer to their sub-culture, and an alternative to ‘classical narrative’. Iñárritu is also very clever in innovating his mosaic further; he continues appeal to his audiences and our times. Whereas Egoyan sticks with his own way of mosaic, and has gradually failed to attract the attention of new audiences, and boring the old fans with his most recent films.

CF: You’ve said that it was difficult to choose which four filmmakers to discuss in your book, and that leaving out directors – especially the female directors, Claire Denis (FRA) and Ann Hui (HK) – was difficult for you. What would you like to say about those two female filmmakers when it comes to mosaic film? Perhaps you’d like to take this opportunity now?!

YhC: Yes! Both Claire Denis and Ann Hui both have very interesting personal experience in – and film production modes of – mosaic. Their understanding of assemblage of spaces through reflection upon history is reflected on screen in their unique manners.

Claire Denis’ Beau Travail (1999) for example beautifully interweaves diverse geopolitical spaces, temporalities, the virtual and the actual, now and then, dream and non-dream, and between-body boundaries.

What makes Claire Denis especially interesting is the diversity of her mosaic space. She strolls between masculinity and femininity, different continents, cultures and even species – as in Trouble Everyday (2001) – as well as different genres, with ease.

The half-Chinese and half-Japanese filmmaker Ann Hui’s context is colonial and post-colonial Hong Kong, within rapidly shifting power relationships within transnational Chinese cinemas.

Ann Hui’s three-dimensional mosaic is a mosaic of understatement. Mainly coming from a strong female gaze, her mosaic assembles different geopolitical spaces, different generations, the empowered and the disempowered, the oppressed and the resistant, places and non-places, tradition and contemporary phenomena.

In her most recent film, Ming Yue Ji Shi You (2017), the characters are interconnected with each other in a such a loose and restrained manner that the mosaic serves rather as a background and an excuse to unfold a bigger historical context. This is very different from Hou Hsiao-hsien’s focus on the interconnected-ness between “places” within closely knit family networks.

It’s a pity that I had to leave their films out within the scope of this book (it was because of overlapping geopolitical contexts with Michael Haneke and Hou Hsiao-hsien). I opted for Haneke and Hou because I felt that they helped demonstrate my ideas of mosaic in a more lucid and thorough way.

Film still from ‘In The Mood For Love’ by Wong Kar-Wai, 2000.

CF: We live in an age where ‘borders’ are in the news daily. Spaces – virtual and physical – are transforming through globalization. Financial systems and technology are shaping ethics and morality. Sexuality and gender identity is no longer “binary”. Workers are transnational “nomadics”, refugees “economic”. Our sense of ‘home’ and national identity is fluid. Things as we know them appear to be unstable and in a rapid state of flux. If, as you argue, mosaic films are the most powerful reflection of this fluidity in geography, society and culture, might now be the perfect time for mosaic film to come into its own? And would you like to see more of it?

YhC: This is a very interesting question. I totally agree that fluidity and instability are the overwhelming reality of everything and everyone nowadays, experienced to diverse degrees and in very different ways depending on geopolitical and socioeconomic contexts.

I think that it is the perfect time for some form of “mosaic”, but maybe not necessarily the kind of “mosaic” – as in the ‘merely mosaic’ narrative that we are used to.

I would definitely love to see “mosaic” being an open-ended concept and more films with creative handling and contemporary understanding of it. Some films that I mentioned above such as Kaili Blues and Ghost in the Mountains are good examples of new possibilities of mosaic, and new understanding of such spaces.

I would even argue that the concept of “the actual” and “the virtual” is open for new interpretation in our time, where augmented reality and virtual reality are giving cinema new grounds for experimentation and new possibilities for story-telling.

CF: And taking that a step further, closer to your experience: you are multilingual, have moved away from your home-of-origin in Taiwan and have lived in several countries and cultures, work as a freelancer across a number of industries and jobs simultaneously, counting linguist, film critic, PhD student and author among them… Given the mosaic of your own life circumstances, it’s perhaps no accident that you are attracted to this topic?!

YhC: Ha ha, you have nailed it completely! This is a project which is very deeply related to my personal experience and the way I look at space.

I really enjoy creating a mosaic and living in a mosaic through my own personal trajectories, which often are very unexpected and surprising! At the same time I am aware of the fact that “mosaic” is a luxury and privilege. I feel very grateful for the opportunity of experiencing “mosaic” first-hand, and I certainly am not trying to define any universal value of “mosaic”. As mentioned in my book, the mosaic auteurs are the privileged ones who can cross borders at will thanks to their socio-economic and artistic status.

In our time when the concept of border and border-crossing is a highly contested one – importantly, the question of who can cross a border is very relevant right now – I think this is worth mentioning. So in my next book I would like to delve into an underprivileged filmmaking mode which is under significant constraints.

CF: If you were going to write and direct a mosaic about your own life (!), who might you get to direct it, and star in it?!

YhC: I have to admit that I’ve never thought about writing and directing a mosaic about my own life, so it is a difficult question!

I guess it would be ideal to get a female version of Michael Haneke to direct it: I like Haneke’s precise and detached manner of mosaic, but I would like it to have a female [filmmaker’s] perspective, say from Ann Hui or Léa Mysius – I was quite impressed by the candidness and sensitivity in her debut film Ava for example.

And it would be nice if Vicky Chen, the 14-year-old girl who won Best Supporting Actress in Golden Horse Film Festival this year for her performance in The Bold, The Corrupt and The Beautiful (2017) could star in it.

I know there is a HUGE age gap between us! But I love her versatility. She is definitely a “mosaic” actress…

Many thanks to Yun-hua Chen for the interview!

* * *

- Interview: Yun-hua Chen

- Words/edit/photos (where credited): Megan Spencer

- Film stills & posters: Short Cuts, A City Of Sadness, Nashville, Babel, Beau Travail, The Sweet Hereafter, Hidden, Lantana, Magnolia, In The Mood for Love.

- Order: Yun-hua’s book ‘Mosaic Space and Mosaic Auteurs’

- Read: an extract of Yun-hua’s book.

- Read: more of Yun-hua’s film writing on her blog.

- Follow: Yun-hua on Instagram

- Out: Australia Day on Digital, DVD, Blu-Ray (January 17).

- Read: more about the cinema of Robert Altman.

I’m also looking forward to bringing you the next two episodes for February and March.

I’m also looking forward to bringing you the next two episodes for February and March.