David Bowie was my first major music crush – obsession, truth be told.

I spent an inordinate amount of time listening to his music, researching it, travelling to obscure suburban record stores to track down titles absent from my collection, taping friends’ records when I was too poor to buy them, and reading about him, voraciously.

It wasn’t always like that.

After years of persistence by my friend Lisa, the penny finally dropped. It was November 1983; we were in our final year of high school. I was at her place and we were listening to ‘Hunky Dory’.

“Can you tape that for me?” I asked, my interest in his 1971 album finally piquing after what had been the umpteenth listen.

“Yes,” she said, rolling her eyes at my inertia.

I rummaged through my school bag. “I think I’ve got a tape.” She rolled her eyes again as I scrabbled around; I was such a dag.

I found it, a C90. On one side was Jean-Michel Jarre’s ‘Oxygene’. The other was blank.

“It should be long enough.”

Thankfully it was. A few days later, after she slapped that homemade tape in my hand – its eleven tracks a magnetic gateway into sweet, tangible, musical otherness – everything would change.

Everything did change.

I still have that cassette, its cover hand-drawn in blue biro.

Thank you, Lisa.

“Long live David Bowie: David Bowie is dead.”

The week David Bowie died was a very strange week, rife with musical immersion, a brother from another planet and eerie coincidence.

Tuesday

Our friend Jeremy arrives from the desert heart of Australia, Yuendemu, where he lives and works recording music and helping to run the local radio network.

A talented musician in his own right, I’d recently interviewed him for an article to help promote his latest EP. In it I’d mentioned David Bowie as one of the prime influences on Jeremy’s sound and approach to music production.

Jeremy also cuts somewhat of an alien-like figure. Having occupied an otherworldly electro-synth musical space since the early-80s, his new EP takes an even deeper dive into lush electronica by way of a major relationship break up. Strains of The Thin White Duke can be heard resonating from deep within the caverns of his back catalogue.

We’d both shared big Bowie love over the years, once even co-DJ’ing a throbbing night of Bowie-inspired music at a tiny DIY club in Darwin: ‘Let’s Dance: David Bowie versus Talking Heads’. Our musical ping-pong match slid into a long night. One of us would play a song by Bowie, the other responding with one by Talking Heads, then switch – the idea being to progressively ‘up’ the dance-ability with each selection. Within minutes of us pressing play the crowd was on its feet. You couldn’t move. It was amazing.

About as far away as you can get from Australia’s northern-most frontier, here he is now, in snowy Berlin, for a ten-day visit. One of the first things we speak about is Bowie’s imminent album release, ‘Black Star’, due out the coming Friday. Having only heard snippets, we weren’t sure about it yet, but excited.

“Why don’t you visit Hansa studios?” I enthuse, surprised at how much like a teenage fan I sound. “There’s an awesome Bowie tour which takes you inside the ballroom where he recorded ‘Heroes’. Then you go upstairs to the main studio.”

I’d been on the tour once before with my husband Oliver, one of Jeremy’s oldest friends from Darwin. (They’d also played in a band together, Cooperblack, with Oliver, German, recruited for his “motorik” drumming ability.) We’d both really loved the tour, and had been surprised at how genuinely entertaining and engrossing it had been. It wasn’t just for ‘Bowie nerds’ either. A seasoned sound engineer and music producer, Jeremy was ‘in’.

“You know we won’t have him for much longer,” he suddenly blurted out. Our eyes met and a sense of dread overcame me.

“I know,” I replied, bewildered by my reflex to agree so quickly.

Where had that come from?

The famous “Meistersaal” ballroom, Hansa studios. Photo: Megan Spencer (c) 2016

Wednesday

We book tickets for Hansa Studios, for the coming Sunday. Turns out Eduard ‘Edu’ Meyer, a thirty-year veteran of Hansa and one of the recording engineers during Bowie and Iggy Pop’s Berlin years (1976-1979) would be there too. (Assisting on ‘Heroes’, he recorded ‘Low, ‘The Idiot’, ‘Lust For Life’ and later ‘Baal’, Bowie’s 1982 inspired Brecht tribute).

Edu was coming to town to help celebrate the release of ‘Black Star’ at Hansa on Friday – also David Bowie’s 69th birthday. To celebrate both, the Studio was throwing a party for industry and the public. Edu decided to stay on for the special tour on Sunday.

We were in luck.

Friday 08.01.16

Friday arrives, and with it some doubt. Would ‘Black Star’ be great?

I hoped so. I hated not liking Bowie’s music. It made me feel like a traitor, which I had been on a good number of occasions since ‘Let’s Dance’ (1983), in my book his last unequivocally great album. It would be a long wait before I could welcome an entire Bowie album back into my smitten heart – 2013’s ‘The Next Day’ to be precise.

Having spent so many of my formative years inside his music, my admiration had never wavered but it wasn’t always easy maintaining the rage (see the Tin Machine years…)

I spend lunchtime watching the two new ‘Black Star’ videos and listening to the music. It makes me feel weird and a bit sick. I don’t get it; I’m confused and viscerally disturbed by both its sound and what I see in the videos. It’s the sonic equivalent of bones breaking.

All I can hear is a chorus from a dark beyond; all I can see is a dying man.

“I think he’s really sick,” I say quietly to Oliver, when I emerge from behind my laptop. “I don’t want to think about a world without Bowie in it.” He looks startled.

Louder, I say to Jeremy, “It sounds like the soundtrack to ‘Suspiria’ – that Satanic death music Goblin did for Dario Argento’s old film.” I sound like an idiot.

I leave the dissonant offerings of ‘Black Star’ and go back to whatever it is I’m working on. I resist my urge to right it off, deciding to wait before giving the album a proper listen. I’ve been wrong before. Patience.

It’s just a piece of music, after all.

Saturday

We hold a small dinner at our place for Jeremy with a few Berlin music friends. Eventually we start ‘juke boxing’ songs from our favourite artists on Youtube and dancing in the lounge room. Shortly into it the selection becomes Bowie dominated: Let’s Dance, Life On Mars, John I’m Only Dancing, Sons of the Silent Age, The Man Who Sold The World, Little Wonder, Five Years… Everyone takes turns picking their favourite.

Buried deep within the recesses of Facebook I find the video Lisa recorded of Oliver and I singing ‘Heroes’ to each other at our wedding in 2011. Jeremy’s there on that country pub stage playing guitar, and so is my friend Philip who on the night spontaneously offered to drum. A ‘new’ friend, James, gave what was nothing short of an heroic performance on ukulele.

Watching closely I remember the liminal atmosphere on that stage: Oliver and I struggle to sing in key, nervous as hell yet loving every minute of this fantastic calamity.

Our mutual love of David Bowie’s music had brought us even closer together when we’d first met in Darwin, three years before. We worked out that, on opposite sides of the planet, at roughly the same time and at around the same age, we’d both moved through the ‘musics’ of Bowie, imbibing each record and artistic ‘period’ with the vigour of the starving.

‘Heroes’ was our wedding present to each other.

Sunday 10.01.16

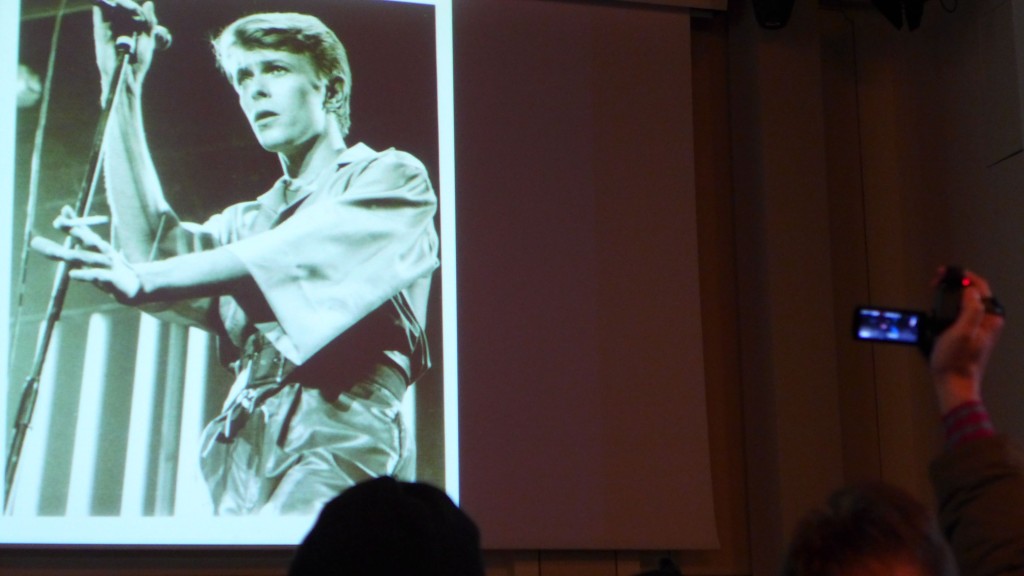

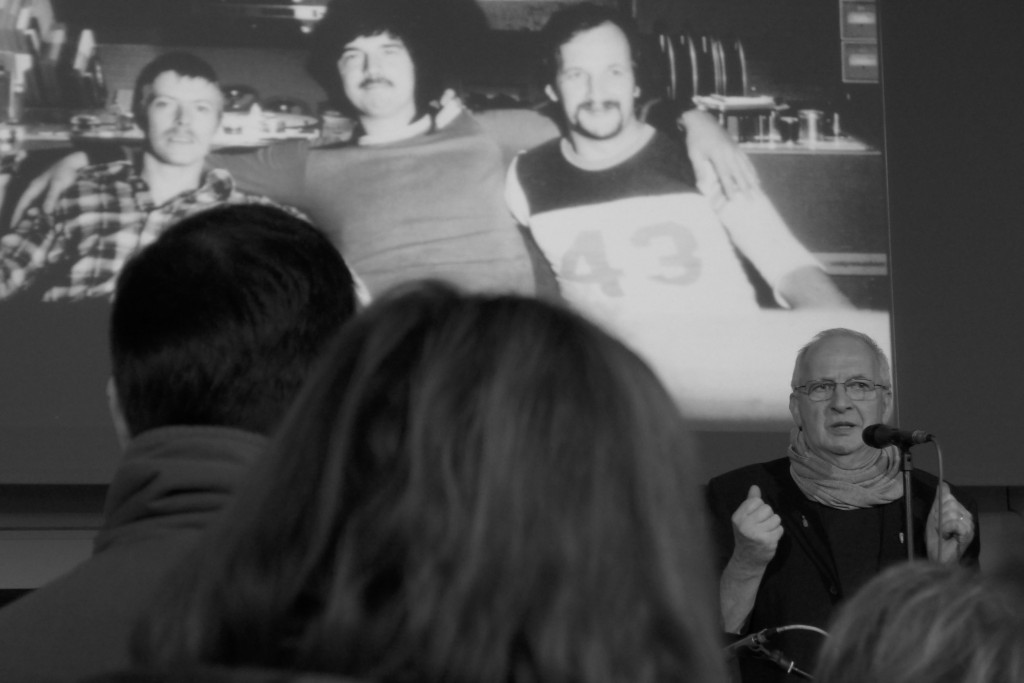

Jeremy and I spend a good three hours at Hansa Studios in Berlin-Mitte with the very hospitable Thilo Schmied (Berlin Music Tours), twenty or so Bowie fans from Europe and beyond, and Herr Edu Meyer, a sprightly 71 years young.

Edu’s voice has been shredded by the “500 interviews” he’d given on the previous Friday, so keen was the German media on the occasion of the Herr Bowie’s 25th studio album release, to have Herr Meyer recount stories of working with his old mate.

We arrive at the historic Hansa building in the unforgiving Berlin cold. Once a guildhall for the Berlin Builders Society, a publishing house and a prestigious concert hall before eventually falling into the hands of the Nazis, Edu stands in front of the still-thriving studio, hoarsely assuring us he’s happy to be here. I wonder how long his voice will hold up – there’s a lot to get through.

Once inside there’s no stopping him – or Thilo. They bat anecodotes and technical details back and forth like tennis pros. Flanked by the grandeur of the Meistersaal – with it’s polished parquet floors, dark timber awnings, high chandeliers and blood-red drapes – both men become living portals into a parallel music world. The walls of Hansa seem to whisper decades’ worth of music folkore and pop legend through them.

Happily, we go there with them. It’s a generous experience.

Edu Meyer & Thilo Schmied at Hansa Studio. Photo: Megan Spencer (c) 2016

A passionate cellist, Edu tells us (several times) that today, he’s given up playing a concert with his beloved orchestra so he can be here to talk to us. Old school and dedicated, he wears a silver whistle on a lanyard around his neck so he can determine the ‘decay’ of any room he might find himself in. To demonstrate, he sounds a French horn from the stage so we can get an idea of the reverb the Meistersaal is famous for – the one and the same producer Tony Visconti gated and captured on Bowie’s monster hit, ‘Heroes’.

Amid the stories a sweet photo emerges. Taken in 1976 during the ‘Low’ sessions in “Hansa Studio 2”, pictured are a moustachio’d Bowie, Visconti and Edu sitting shoulder-to-shoulder behind a mixing console.

Brandishing a glass of scotch, Bowie looks healthy as an ox. They’re happy and at the start of something big: you can see it.

Jeremy and I go home sated and happy. It was snowing again. Berlin was positively splendid.

Monday

8am. Jeremy knocks on our bedroom door.

“Come in!” I say, my voice croaking from having only just woken up.

Standing there in his underpants, in the doorway, he says softly, “Bowie’s dead.”

“What?” I struggle to sit upright.

News had just come over…

“What??”

“Yeah, he died, yesterday. Of cancer. No-one knew.”

Our startled eyes meet again. “This can’t be real”, I say. Yesterday we’d been retracing Bowie’s footsteps at Hansa, secure in the knowledge he was still alive. This changed everything.

This made him a ghost.

“A world without Bowie in it…” The unthinkable had happened.

A giant had fallen.

Hauptstrasse 155 memorial. Photo: Megan Spencer (c) 2016

Later that morning, about to set forth into the day, Jeremy grabs his ‘Man Who Sold The World’ tee shirt out of his rumpled duffle bag.

“Should we hang it out the window like a flag?” he asks.

It’s about to snow again. We need to mark this day, publicly. I light a candle and place it in the window. I hook his tee shirt high up over our balcony. I want to make sure it can be seen from the street.

A rusty love-heart garden ornament swings by its side.

Immediately the footpath in front of Bowie’s old apartment in Berlin-Schöneberg becomes a makeshift shrine. Elderly ladies and shopkeepers from the kiez look on in amusement as people come, and keep coming, lighting candles and placing flowers, photos and hand-written messages in front of the building.

The döner shop next door does a roaring trade.

TV goes nuts. Every second song on the radio is his. Facebook clogs with Bowie-related posts. Tributes pour in from his friends – famous and otherwise – and mourning fans. Old videos surface. No-one can quite believe it.

In slow motion I again trace back time to realise just how much attention Jeremy and I had given David Bowie over the past week. While we’re ‘in deep’, we do have lives – and perspective. It’s been intense. Unusual.

Could we have subconsciously been ‘pre-mourning’ his passing? Is it possible to do that – and for someone you don’t even know? Had his work meant so much to us that we were somehow able to intuit his death, like dogs barking the week before a big storm?

It felt like it.

I recall how disturbed I’d felt by ‘Black Star’, that “Satanic” soundtrack. But there it was, right in front of us all: he’d told us he was going. Little wonder it had got to me.

This is what David Bowie once wrote about hearing George Crumb’s ‘Black Angels’ composition for the first time:

“…Bought in New York, mid-70s. Probably one of the only concert pieces inspired by the Vietnam War. But it is also a study in spiritual annihilation. I heard this piece for the first time in the darkest time of my own 70s, and it scared the bejabbers out of me.

“At the time, Crumb was one of the new voices in composition and Black Angels one of his most chaotic works. It’s still hard for me to hear this piece without a sense of foreboding.”

“Truly, at times, it sounds like the devil’s own work.”

Bowie street memorial, Berlin. Photo: Megan Spencer (c) 2016

Lisa is the first person to contact me. Her texts from Australia fly thick and fast.

“LONG LIVE BOWIE; DAVID IS DEAD.”

“I know you wore the grooves out of my Bowie albums….”

“Who writes their own departure tune, delivers it on their birthday, then – departs! Who fucking does that? Bowie, that’s who!”

“Who’s going to write my life lyrics now?

“Wham bam, thank you ma’am!”

Referring to ‘Black Star’, she writes: “Death Dirge… I didn’t like it… Now I see why.”

The exchange lasts an hour.

A need to commune takes hold. Reflexively I send an email to my friend Philip – the drummer from our ‘Heroes’ wedding ‘gig’. We’ve known each other since 1987.

A prolific music composer, drummer, artist, long-time Bowie aficionado, glam historian and culture writer, Bowie runs deep in his bones. He’s been into him since the start, having also owned a stellar collection of posters back in the day. Years ago, when he told me he’d sold them to a vintage music store, I couldn’t get down there quick enough to pick the eyes out of them.

I send Phil a link to a clip of David Bowie on The Don Lane Show. It was 1983 and Bowie was in Australia on the Serious Moonlight tour, blonde, be-suited and riding the wave of his biggest mainstream breakthrough. He was charming and feisty. It was “the lanky Yank’s” lucky day.

Turns out he’s in Paris. “The metro subway here has long walls of posters advertising the ‘Black Star’ album,” Phil tells me.

“It feels like walking through a mausoleum.”

Monday keeps going. Our Berlin friends rally. Most are musicians or in related fields. One announces a spontaneous Bowie karaoke tribute night: “Joyful Wake For The Thin White Duke”.

“Put on your red shoes and dance the blues…” she touts. “8pm – 5am, at Monster Ronson’s”, Berlin’s most in/famous karaoke facility. Sam, the organiser, worries whether there will indeed be room for the group, anxious an unruly mob of like-minded Bowie acolytes might crowd hers out.

They don’t get a booth until 10.30pm. Then it’s on for young and old. Guts are sung out, tears are shed. Joy is felt. It’s all about the music. Jeremy is there with Oliver.

Monday into Tuesday

Fresh from singing every Bowie song in the book Jeremy and the remaining karaoke stragglers stumblebum their way across town in black ice to the Hauptstrasse 155 street shrine. It’s 4am and a digital footprint of their early-morning pilgrimage surfaces on my Facebook feed.

“He’s hardcore,” I whisper to myself, looking at the dark, pixelated image of glowing candles and frozen flowers he posted only hours before.

Love you till Tuesday.

Bowie memorial, 4am, January 12, 0 degrees Celsius. Photo: Jeremy Conlon (c) 2016

Friday

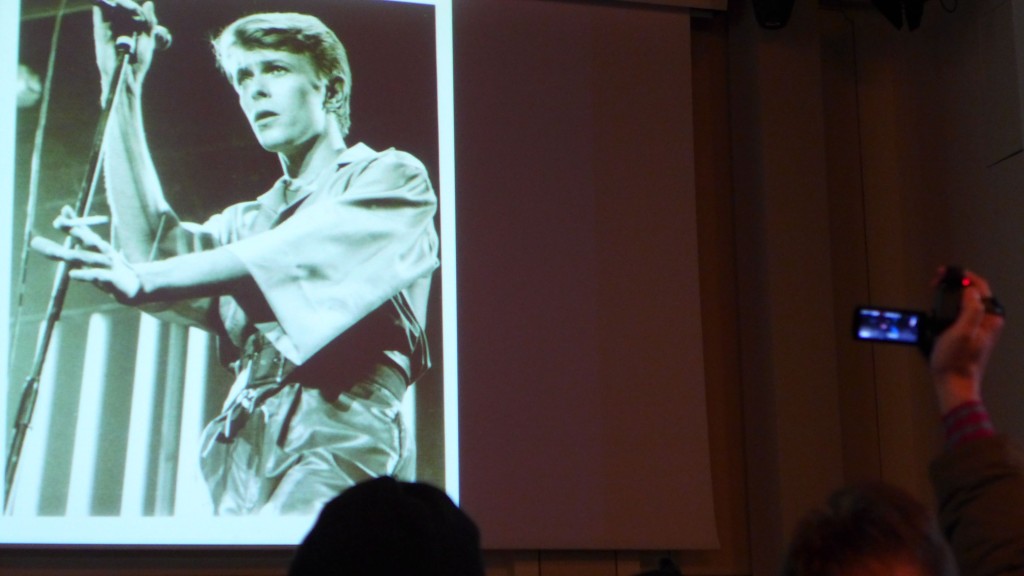

I’m back at Hansa. The Studio and Thilo have organised a mass public memorial inside the iconic Meistersaal. Berlin was Bowie’s “spiritual home” and Hansa a sacred site.

The media is out in full force. Hundreds of people line up outside eager to be the first inside, come midday. Oliver and I are among them. It’s a big ballroom; there’s enough room for everyone. People come and go across the day to pay their respects.

Edu is still here – I’m guessing he hasn’t left since the previous Sunday. On stage he shares some of the emails he and Bowie exchanged across the years: they’re funny and personable, with genuine camaraderie.

As a musical tribute he plays cello to the mournful instrumental track, Warszawa. He’s more or less in the same spot where he recorded it for Bowie some forty years prior, for the album ‘Low’.

Fans and others then take to the mic to share stories. A Portugese woman in silver boots belts out a moving acapella version of ‘Space Oddity’ and there’s not a dry eye in the ballroom. I see Edu and Thilo standing sombrely side of stage.

In the quietness of the moment, shock and disbelief show on their faces. Thinking back to last Sunday – that Sunday, January 10 – and the coincidence of us gathering in this space to celebrate David Bowie’s music and life, on the day he leaves the world, is an eerie one. That ballroom is so historically charged by his presence and music. That must have crossed the mind of everyone in that tour group at some point during the week. It certainly did mine.

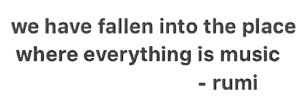

A slide show of images of David Bowie from across the years beams onto the screen hanging over the candles and roses on the stage below.

Somehow Jeremy’s blurry ‘4am at Hauptstrasse’ photo winds up in the mix.

Hansa Memorial. Photo: Megan Spencer (c) 2016

Edu Meyer at Bowie memorial Hansa studio. Photo: Megan Spencer (c) 2016

Crowd in Meistersaal, Hansa Bowie memorial. Photo: Megan Spencer (c) 2016

Fan on stage at Bowie memorial, Hnsa studio. Photo: Megan Spencer 2016

A fan signs the Condolence Book. Photo: Megan Spencer (c) 2016

Space Oddity, acapella. Photo: Megan Spencer (c) 2016

Roses on the stage, Hansa memorial. Photo: Megan Spencer (c) 2016

Jeremy goes back to Australia. He leaves early Wednesday morning. We both acknowledge the strangeness of the week and the palpable sense of sorrow and loss. Bowie really is our hero.

“So weird I was here, in Berlin, this week…” he whispers as we hug goodbye.

“It makes perfect sense,” I nod back.

He and I are a bit ‘fey’. We needed to be together, for this.

Farewell to “The Cosmic Yob”.

“David Robert Jones” was a suburban boy bound for a middle management future who one day discovered the local record store and took off to the stars. His imagination caught fire with the tindersticks of musical discovery. Read any interview with Bowie: he jumps at the chance to pay tribute to an intricate array of influences and heroes. They transformed his life and, helped him live a life less ordinary.

When I invited David Bowie’s oceans of music to wash through me and settle into my DNA, everything I knew also changed: the world, myself, and my understanding of both.

For the first time I experienced music as a real ‘embodiment’. It filtered into my senses, thoughts, emotions and physicality. It pushed me beyond what I’d previously known of art and popular culture. And there were chapters and chapters of this stuff – a mutable flow, all stemming from the energy and curiosity of just one artist.

It transformed me. It became part of me. David Bowie was my musical ‘rite of passage’. I am so thankful. It feels great to live in a world “where everything is music.”

Don’t worry about saving these songs!

And if one of our instruments breaks, it doesn’t matter.

We have fallen into the place where everything is music.

The strumming and the flute notes

rise into the atmosphere,

and even if the whole world’s harp

should burn up, there will still be

hidden instruments playing.

So the candle flickers and goes out.

We have a piece of flint, and a spark.

This singing art is sea foam.

The graceful movements come from a pearl

somewhere on the ocean floor.

Poems reach up like spindrift and the edge

of driftwood along the beach, wanting!

They derive

from a slow and powerful root

that we can’t see.

Stop the words now.

Open the window in the center of your chest,

and let the spirits fly in and out.

— Jalaluddin Rumi, ‘Where Everything Is Music’

To contact or send comments, email:

hello@themeganspencer.com

Our Berlin Bowie flag, at half mast. Photo: Megan Spencer (c) 2016