It’s amazing who you meet in Berlin…

Artists are drawn to the city as if it were a kind of mythic, spiritual ‘big top’, seeking artistic inspiration, like-minded community and creative challenge. Something I’ve written about time and time again here at Circus Folk!

Mark Ogge is one such ‘pilgrim’. Hailing from Melbourne, Australia – and the brother of one of my dearest friends – Mark’s an “internationally renowned” mid-career artist with a passion for making images inspired by “the rich history of fairground and theatrical art”, the circus, vaudeville and Commedia dell’Arte.

Having studied all of the above, in 2001 he painted the Famous Spiegeltent Facade under which thousands have sat during Melbourne festivals (and elsewhere around the world). Also iconic carnival figures at St. Kilda’s Luna Park, and – with an international commission in 2016 – he brought to life the stunning travelling ‘Circus Automata’ at Melbourne Arts Centre.

So I kind of wasn’t surprised to see him in Berlin. He was in the right place.

With “a strong interest in German art” and on a self-imposed artist’s retreat, he found a supportive residential studio at Hidden Institute artist kollectiv in Neukölln. He was there to complete a series of 30 “smaller” works inspired by a long-standing fascination for Melbourne’s Luna Park and a recent two-month stay in Coney Island.

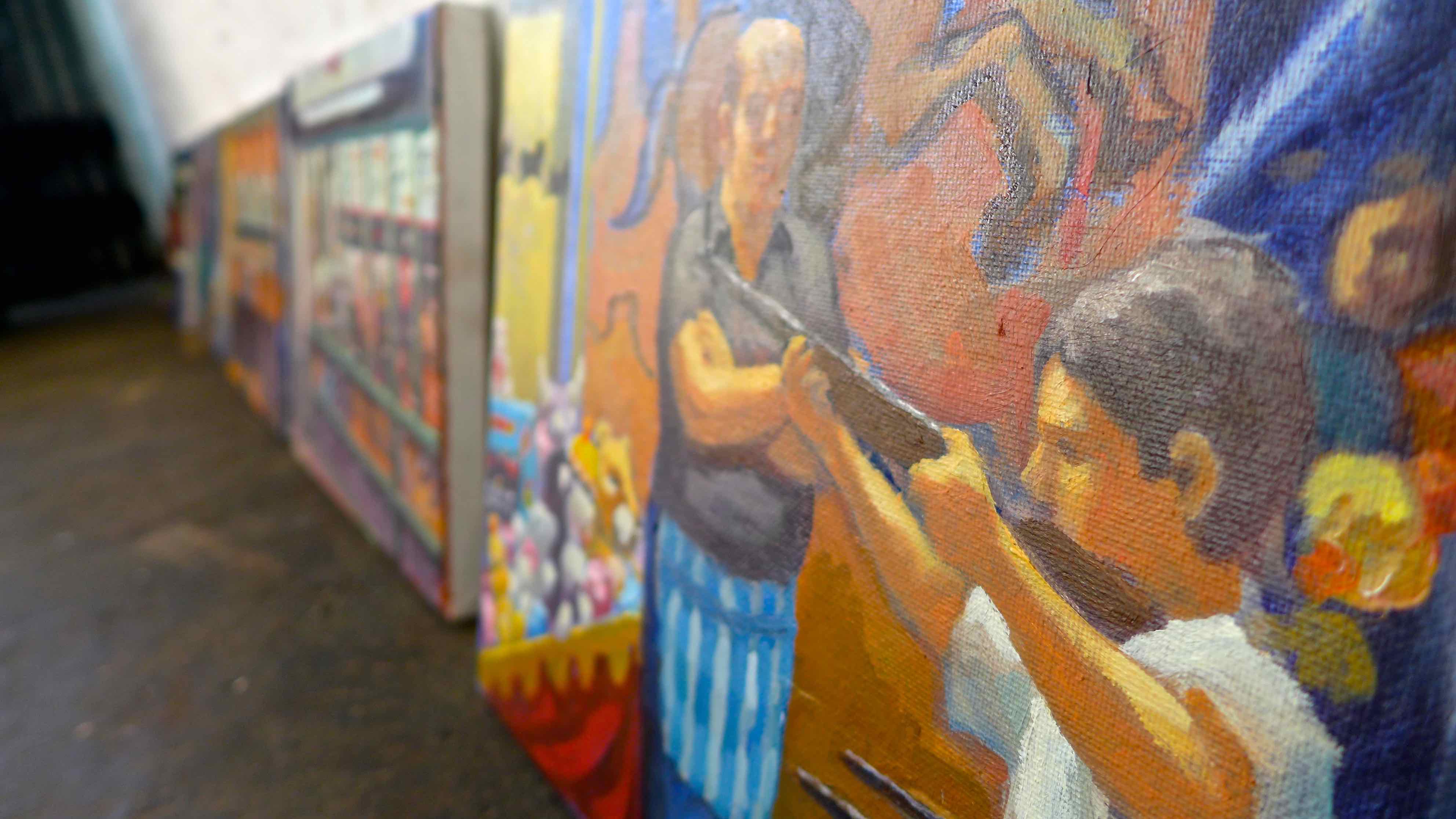

From Mark’s Coney Island series painted in Berlin, 2017. Photo: Megan Spencer (c) 2017

Most importantly, he was there to rekindle a painting habit which in recent times had been sidelined by the time demands of environmental lobbying, another vocation Mark is equally passionate about.

Inspired by “literally hundreds of favorite artists” and with a distinct, mercurial style, Mark’s oil paintings are in-demand. He receives commissions – often large-scale and festive – from all over the world. His Berlin paintings however depict falling down theme parks glowing quietly with muted colours, ‘last leg’ landscapes and lonely figures.

Filled with hope and disappointment, celebration and pessimism, they distill a paradoxical kind of nostalgia. Outwardly they shine with the allure of symbols and structures that contain fantastic worlds. On closer inspection they reveal a stillborn, shabby existence falling down around our ears, forlorn figures lost in a world of broken promises.

It’s not so much nostalgia but what Mark calls “solistalgia”, “a form of psychic or existential distress caused by environmental change.”

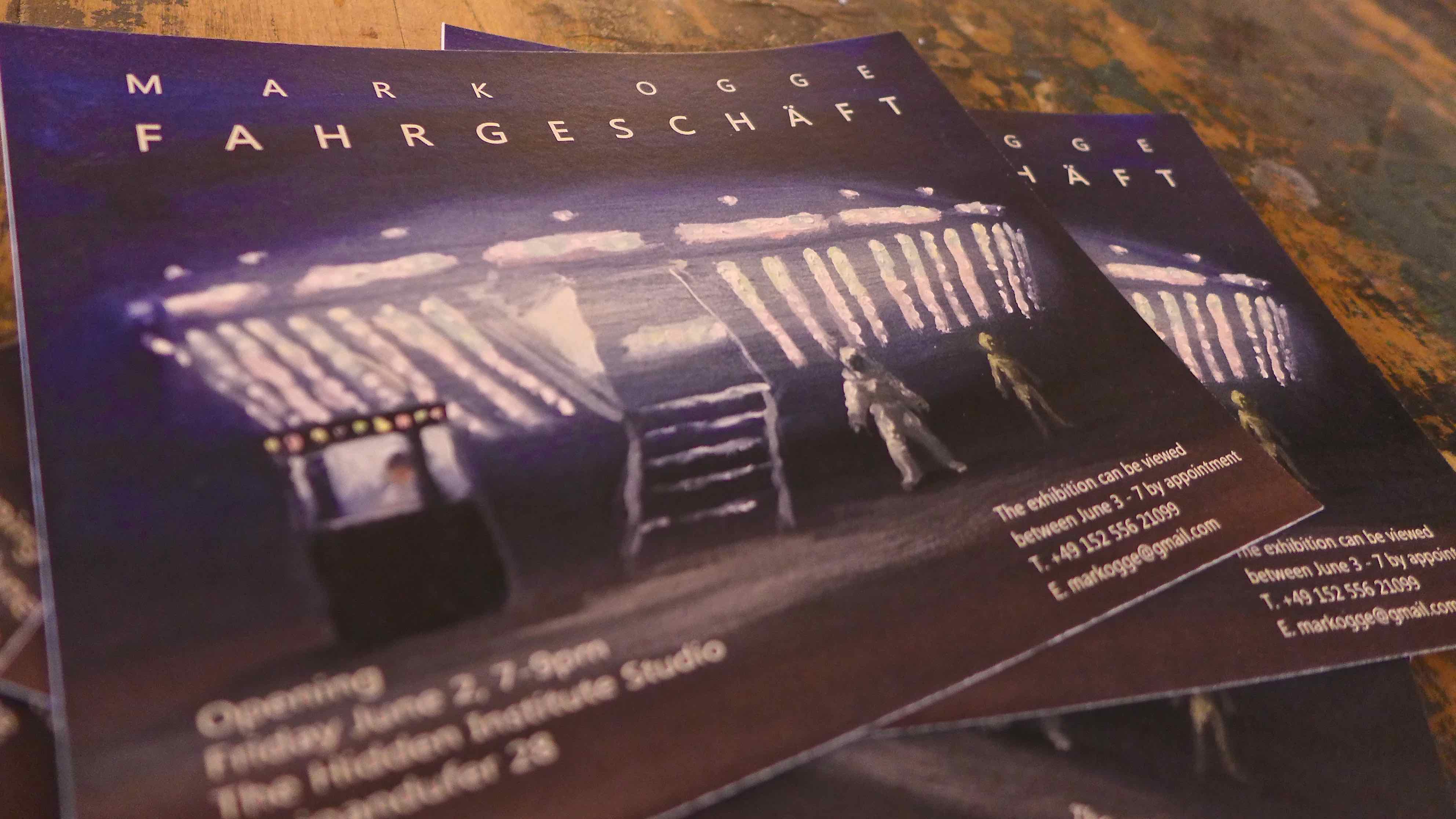

Mark painted them during an intensive six weeks. Then exhibited, calling the show in German, Fahrgeschäft (“Amusement Ride”). It was simply beautiful, heart-achingly so, especially when it came to the paintings of fairground ride “The River Caves” from Luna Park.

They evoked in me sharp pangs of of loss. My Mum grew up on the rough, pre- and post-war working class streets of St. Kilda. Luna Park gave her much-needed respite. The River Caves ride was her favorite – mine also, years later. These were paintings she would have loved. Wiping away tears stinging with 5 ½ years worth of grief, I wished she could appear by my side to see them too.

I did what any person secretly crying would do: rest my head on the pillow of a kind room. The opening for this exhibition of small, intimate, personal work was a small, intimate, personal affair. People huddled around the work for hours, laughing and chatting, happy to support such a personal endeavour.

Bolstered by his time in Berlin and with his practice re-energised, back in Melbourne Mark runs social “ad hoc painting evenings” with friends and has again immersed himself in painting. “Excited,” he’s working on “10-20 very large paintings” saying they are a “watershed”.

Berlin helped him get there…

Circus Folk: Mark, it seems that you and I share a big ‘thing’ for sideshows, amusement parks, fairgrounds and circus folk! When did your interest in this kind of subject first kick in? And what draws you to this world?

Mark Ogge: The way I learned to paint was painting and drawing from life. I would go out every day and find a subject that I liked, and draw and paint it. It might be a tree, a corner of a back yard, an industrial landscape, a service station – just anything that I felt drawn to, that resonated for me.

One day I went to the Sole Brothers Circus that was set up on the corner of Punt Road and Swan Street in Richmond [Melbourne], and did a series of paintings of the tent, the stalls around it, the caravans… I felt a real fascination for the subject matter [then] started drawing and painting at other fairgrounds like the Royal Melbourne Show and Moomba.

I found it incredibly rich subject matter: visually – full of light, colour, people, shadows – but also full of metaphor and symbolism.

CF: Do you remember the first time you saw your first circus or fairground?

MO: My main childhood memory was a moment at the Royal Melbourne Show. I remember it distinctly: standing outside the Chamber of Commerce pavilion (the that was one full of show bags!) Until that moment everything had seemed magical and infinite, and then suddenly the magic dropped away and I saw it as somehow shabby and immensely lonely.

I’m not sure if my perception was changed by some other event or anxiety in my life at the time, or whether it was a moment of actual insight, but it was a powerful experience for me.

To me this experience is emblematic of our way of seeing the world: as children we are gripped by wonder, everything is magical. Then as adults we shift to a more ‘knowing’ perception, seeing the shabbiness, crassness [and] monotony.

But we are still capable of experiencing intense engagement and wonder, and often shift between the two.

“River Caves, Mawson Expedition” by Mark Ogge (2017). Photo: Megan Spencer (c) 2017

“The Gravitron” by Mark Ogge (2017). Photo: Megan Spencer (c) 2017

CF: Yes – your work has been described as a “dichotomy between enchantment and disillusionment”. For someone new to your work is that how you would describe it?

MO: My work aims to recapture the sense of wonder that a child can experience, but also the ordinariness behind it.

Take the painting of the Gravitron that I painted in Berlin: the Gravitron is an actual fairground ride in Australia. On one level, for a child, the Gravitron is a wondrous apparition, full of the excitement and mystery: space travel, aliens, the promise of some extraordinary experience once we walk up the ramp and enter…

But we also know that the ride cannot fulfill this. The bored woman in the ticket box [see above] hints at this underlying ‘ordinariness’. Yet to a child the ticket booth is a glowing portal to a transcendent experience.

Layered over that are the metaphoric associations of the thing itself, suggesting the optimism of space travel but fear of the unknown – aliens! It’s comic but also somehow deeply symbolic of our aspirations and fears.

Fairground imagery is often powerful and full of symbolism. To attract people it needs to tap into our desires and fears. Think of the ghost trains and haunted houses as archetypal images of fear and death, or the river caves creating exotic wonderlands of places we would love to visit.

And then there is the artificiality… When we go to a fairground we’re surrounded by an entirely artificial environment: everything is plastic, steel, paint, lights and amplified recorded sound. And in that sense it’s a metaphor for how we have transformed the natural world into an artificial wonderland. This results in excitement, spectacle and illusion of plenty, but also a deep ‘solastalgia’.

The artificial world we inhabit creates a deep anxiety and sense of loss for the natural world, even if these feelings are on a largely unconscious level. So for me the fairground is a metaphor for this, like the world in ‘miniature’.

“Neptune, River Caves”, painting by Mark Ogge (2017). Photo: Megan Spencer (c) 2017

CF: Who are some of your painting heroes?

MO: I have pretty broad taste – I’ve literally got hundreds of favourite artists! I particularly love Quattrocento Italian Renaissance painting: Giotto, Piers Della Francesca, Bellini, Mantegna, Lippi. [I love the] the simplicity and clarity.

Also early Modernism: Manet, Picasso, DeChirico and many others. To me this was an incredible period of inventiveness and vitality as artists grappled with representing a world in rapid change. I particularly love Picasso’s Blue and Rose period paintings. It’s the simplicity and iconic beauty of the figures, also reminiscent of Quattracento Italian painting.

German Modernism: Max Beckman and Otto Dix are both extraordinary.

Leonora Carrington is a particular favourite of mine. I find her idiosyncratic world of magic and symbolism endlessly fascinating.

For me the greatest period of Australian art in the Western/European tradition was ‘The Angry Penguins’, particularly Nolan, Hester, Boyd and Percival. I think Sidney Nolan is Australia’s only artistic ‘genius’ in the western tradition. I’m constantly staggered by his lyricism and mercurial inventiveness, creating work of incredible sophistication in an almost ‘folk art’ idiom.

But I think Emily Kngwarreye is probably Australia’s greatest artist. She started painting at 60 years old, and over a ten-year period did a body of work that puts just about everyone else to shame – often huge, monumental works, always immensely aesthetically inventive.

Viewed simply as abstract paintings they’re phenomenal – and that’s [even] without really being able to fully appreciate them on a level of their actual meaning, in terms of [the] Indigenous people’s connection to spirit and place.

And contemporary art: Kerry James Marshall, Anselm Keifer, Peter Booth, Frank Aurbach, Neo Rauch and Christoff Ruckhaberle come to mind.

“Fahrgeschäft” vernissage, Hidden Institute. Photos: Megan Spencer (c) 2017

CF: Other than those you’ve named, what has your personal aesthetic and style been informed by?

MO: Rather than ‘try’ to develop a style or aesthetic, I’ve tried to express my vision of the world as well and honestly as I can. I see painting as a quest to find ‘a natural way of expressing’ as distinct from creating a pastiche of other artists – or, trying to be ‘original’.

What I take from other artists is finding better ways to express my own vision by understanding the craft of aesthetics and image making.

In Berlin I saw a talk by [African-American artist] Kerry James Marshall [whom I consider] one of the best living artists in the world. Asked why he looked to the “canon” of western art for inspiration rather than rejecting it or looking to a “black” tradition, he said that he had a moment of understanding when visiting the Uffizi [Gallery in Florence].

Surrounded by Quattracento Italian paintings he realised that some were great images and others were not. For example the Giottos and Botticellis were superior to many of the paintings around them.

He said at that moment he realised there were “things” that made one painting better than another – the craft of aesthetics (my words) – and that he needed to learn from these artists to understand those things in order to make the powerful work he wanted to make.

And he certainly did!

Big top painting by Mark Ogge.

So I guess the answer to the question is that I hope my work remains a true expression of my perception of the world, but that I can express it more powerfully by understanding great art from the past.

CF: In addition to your own paintings, you were also commissioned to paint the façade of The Famous Spiegeltent Facade that not only appears at the Melbourne Arts Festival every year, but travels to the States as well. Can you tell us a bit more about that?

MO: In a way I do two quite separate things. The first is doing paintings that aim to express something – hopefully something important! – about the world and about myself. The second is what I’d loosely describe as ‘theatrical commissions’, of which the Famous Spiegeltent Facade is one example.

These works are designed to entertain and create an atmosphere and character for a place or venue like the Spiegeltent. The facade design of the Famous Spiegeltent has life-size vaudeville, cabaret and Commedia dell’arte characters [professional, travelling circus folk popular in Italy 16th-18th century], to create a world of mystery and intrigue that people want to enter. And [that] reflects the atmosphere inside the tent.

This work draws on the rich traditions of fairground art and theatrical art, Commedia dell’arte, circus, cabaret and the like.

I love these traditions. For me the characters of sideshows, circus and Commedia dell’arte are avatars for ourselves. We all have a bit of ‘The Strong Man’, ‘The Half-Man Half-Woman’, ‘The Diva’, ‘Pierrot’, ‘Magician’ or ‘The Show Girl’ [in us]. It’s why the Commedia dell’arte was so successful: they would go from town-to-town playing the same characters. And in every town the audience would recognise local personalities or aspects of themselves. They’re timeless and universal.

Because I spent many years painting theatre scenery I was able to immerse myself in the tradition and craft of theatrical art, and to develop the skills to work on a very large scale. And I’ve been lucky enough to have the opportunity to create large scale works of this type thanks to [commissions from] The Famous Spiegeltent’s and Melbourne’s Luna Park.

CF: What are some of the biggest challenges faced by painters nowadays? Is it still as popular a medium for artists to work in? Or are there ‘competing forces’ (ahem digital, conceptual) at work that have diminished its “cache”?

MO: For me it doesn’t matter what medium people work in. Painting is just one of many possible mediums. The test is whether an artwork is aesthetically compelling and has resonance. The reason I use paint/drawing and so on is that [for me] it’s the most direct, tactile and versatile medium.

It allows extraordinary freedom. An artist can create any world or image they’re capable of imagining and realising in the medium, with infinite variation. It also allows for expressing atmosphere and mood with enormous subtlety. By contrast [and this is just my personal taste and opinion] I find installation very limited in its expressive potential by its physical constraints, particularly in its subtlety. However there are [also many] really great artists who do fantastic installation work (Louise Bourgeois and Anselm Keifer spring to mind).

Digital and video allow more subtlety but in world utterly saturated by video and digital imagery, to me, it makes them pretty unappealing.

Personally, I find conceptual art unsatisfying. It tends to be aimed at making a political or sociological point about racism, colonialism, power, sexual politics and so on. Although I share the values of most of this work [often] I find the experience of the artwork leaves me cold. And I don’t think it has much – if any – value in bringing about social change, which is presumably the intention with much of it.

[I believe that a] sophisticated political or sociological discourse is far more suited to writing.

Conceptual art is now “the academy”, so these spaces are dominated by highly conceptual art. Where it worries me is that there are actually limited public exhibition spaces for contemporary art. [I also acknowledge] it’s difficult for artists to say this without it sounding like being disgruntled for not getting enough attention. In my case I feel very lucky: I can make a living from my painting and have been very well supported throughout my career.

[So] I’ve got no complaints! But [these days] I rarely see painting or any visual art that even attempts to engage with aesthetics in public contemporary art spaces. And [again, it’s just my personal opinion!], I think we are all the poorer for this.

CF: You have been a working artist for some time but you have also “recently’ begun working in the “political/environmental” industry…

MO: Being an artist was my sole profession until 10 years ago. However I became so concerned about global warming that I felt the need to act on this. For several years I worked in a volunteer capacity helping to build up a climate advocacy NGO, Beyond Zero Emissions. This became successful and ultimately I took on a paid role and then moved into a position at the Australia Institute working on challenging coal and gas mining in regional Australia.

Port Augusta power plants north view painting by Mark Ogge (2013).

In Australia huge coalmines and unconventional gas fields are largely approved on the basis of claims by the companies that they will provide a lot of jobs and economic benefits. In fact these claims are almost always vastly exaggerated and these mining projects can do a lot of damage to the rest of the economy. I work with economists at The Australia Institute who provide research to challenge the claims of the coal and gas companies; my job is to go to regional areas where mines are proposed and challenge the mining industries claims in public talks, with local businesses, council, farming groups and so on.

Admittedly it’s a strange role for a visual artist! But I have an aptitude for it and I think its important work. I also get a lot out of it! In a strange way it actually complements my life as an artist because it can be quite isolated. This allows me to work with amazing people from all walks of life all over Australia. And intellectually I find it interesting and challenging.

Working in this field is also very demanding so it has been challenging to maintain my art practice as a result. However I have continued to exhibit regularly and undertake major commissions over this time. Although this work is very important to me and I will continue to be involved, my aim is to wind back the environmental work and focus more on painting.

CF: So what is it then that you love about painting – and the process of it? What is it that keeps bringing you back?

MO: I find painting a profound mode of communication. When I see great paintings, they create an imaginative world and communicate an understanding of the world and humanity that is different to what can be communicated in any other mode – like say writing or music. It is contemplative and usually can’t be grasped at a glance, but [it] can communicate at a deep level.

There’s enormous imaginative freedom in painting. Painting can depict anything within the confines of the picture-frame, limited only by the imagination and skill of the artist. The imaginative worlds created by painting are almost limitless. Think of the world of Bosch, Van Gogh, Monet, Leonora Carrington, Morandi: they are utterly different universes, but all compelling and instantly recognisable to the point that they have become part of our collective imagination.

Painting is emotionally expressive. It can be applied with the elegant simplicity of Fra Angelico, the sensuality of Soutine, the harshness of Ensor or Dix, the delicacy of Watteau – or anything in between. And all these ways of ‘applying the paint’ [also] express emotional nuance, similarly to how different types of music evoke different emotions.

I also love the directness, tactility and beauty of the medium.

Circus folk roll call at “Fahrgeschäft” vernissage, Hidden Institute. Photo: Megan Spencer (c) 2017

CF: Why did you come to Berlin?

MO: I wanted to work for a while on my own work in an interesting place other than Australia – and where I had access to great art collections. I [also] really love German art and find Germany a fascinating place culturally and historically.

I’ve always had a strong interest in German Art – Max Beckman and Otto Dix are two of my favourite artists. I’m also a big fan of contemporary German painting, particularly Keifer and some of the Leipzig painters, Neo Rauch, Daniel Richter and Christoff Ruckhabrle. Having access to these collections in both Leipzig and Berlin was great!

In part I came to Berlin for the same reason as a lot of other artists do: that it’s possible to [access] studio space that is reasonably affordable. Berlin is also a very dynamic city that is still creating itself whereas many [other] European cities – which I [also] really love – are in a sense completed ‘works of art’. The relative dynamism of Berlin appealed to me as a place to work. It’s also somewhere with an extraordinary recent history.

CF: What was your take on the European (and Berlin) art culture? And did you find it inspiring?

MO: I really enjoyed meeting a lot of local artists who were so open and generous with talking about their practice. And I found the “important” collections in Berlin, elsewhere in Germany and Europe, enormously inspiring. I’ve got a particular interest in German Moderinsim [so] I loved the great collection in the Gemalgalerie. Seeing the Leipzig School painting was a real highlight.

[As I’ve said] I’m most interested in painting or visual art that is aesthetically engaging. I think there’s undoubtedly a lot really great contemporary artwork being done in Germany and Europe, but it’s surprisingly hard to find because highly conceptual art is so dominant.

I don’t think this is a problem peculiar to Berlin. I visited the Venice Biennale and documenta in Kassel which both profess to showcase European (and global) art, and found both pretty much entirely academic conceptual artwork.

Berlin party balloon. Photo: Megan Spencer (c) 2017

CF: Working in Berlin, was it much different to say having a studio in Melbourne?

MO: It was important for me to work away from Melbourne, in part to refresh and get some distance from my other occupation in political/environmental work and really focus on painting.

It’s so great to have access to great collections while I’m painting. For instance to be able to go to the Gemaldgalerie in the morning with access to extraordinary Titians, Bellinis and Holbeins, then paint in the afternoon – it was an enormously refreshing experience for me. It enabled me to re-engage with my work and take real lessons from the great artworks I had access to.

I only had about 6 weeks to paint – which is a very short amount of time for a body of work. But given that limitation I’m really happy with the work I did, and that there were some important developments that I would not have achieved in Melbourne.

CF: Please tell us a bit about the new series of works you made on your stay in Berlin… What inspired those pictures?

MO: The paintings are a combination of images I’d been working on in Australia and the US immediately prior to coming to Berlin. I began with 30 small studies of images I wanted to develop. Some were images I have been developing in one way or another over a long period, and others were based on drawings I made in Coney Island in the US.

I’m particularly pleased with the Gravitron image, and the River Caves series, which I will develop further this year.

I also worked on a series of images that I developed at Coney Island. I was there in winter when the park was closed – an incredibly atmospheric time. The huge fairground rides along the foreshore were deserted and enveloped in snow and fog. I think the studies of the Thunderbolt [ride] are successful and I’m looking forward to doing larger versions.

Besides works based on the fairground, I did a lot of drawings of street life in Coney Island. It’s quite a gritty place and gave me a glimpse into a pretty real part of America. I’m really pleased with some small studies I did of Dunkin Donuts, Checkers and Nathan’s, [which] I’ll also take further.

[Right now] I’m working on 10-20 very large paintings of images I have been developing over the last few years. I’m really excited about this new body of work; I think it will be a real watershed. I’m going to spend the next 12 months working on them and look forward to exhibiting them in 2019.

“Spiegel Automata” (2016) by Mark Ogge.

CF: And – did you manage to visit any fairgrounds in Berlin?!

MO: The only fairground I visited was the temporary fairground in Hasenheide near Hermanplatz! I did some drawings there. Actually – it wasn’t that different to Australian fairgrounds, they’re pretty universal I guess!

They had a particularly good ghost train that I’m sure I’ll do a painting of at some stage!

Many thanks to Mark Ogge for the interview!

* * *

- Interview/paintings: Mark Ogge

- Words/Edit/photos: Megan Spencer

- Visit: Mark’s website

- Like: Mark’s Facebook page

- Follow: Mark on Instagram

- Read: about Mark’s Circus Automata exhibition

- Buy: Mark’s prints

- Commission: Mark’s work

- More: about Emily Kngwarreye

- Discover: Beyond Zero Emmissions

- Some clarifying changes were made by the editor to the above text after publication – and the reinstatement of an original question, incorrectly omitted – to give proper and accurate context to the answer.

Tagged: art, artist, circus automata, commedia dell'arte, famous speigeltent, mark ogge, painting