Berlin is no stranger to ‘cross-cultural exchange’. An historical “hub” between Eastern and Western Europe, immigrants have been steadily arriving for over 800 years.

You could say the city was built on it.

Something former mayor Klaus Wowereit was supremely aware of when in 2003 he proudly proclaimed the German capital “poor but sexy” to the entire world.

Perhaps ‘crass’ in the eyes of some, “Wowi” was not only hoping to encourage economic immigrants (ie big business, tech start ups and the eventual “roamer workforce”) to set up shop and part with their cash in his “impoverished” city. Simultaneously he renewed and acknowledged Berlin’s longstanding historic commitment to welcoming cultural and creative migrants as well.

Artists, performers, thinkers, writers, poets, punks, workers, musicians, outcasts, academics, philosophers, explorers and those at the vanguard of every creative pursuit imaginable, have their left homes from every country imaginable, to migrate to Berlin, bringing with them not only financial but cultural capital. (Don’t just take my word for it: read Stuart Braun’s excellent historical examination of this, ‘City Of Exiles‘).

For better or worse this “creative wealth” is what gives Berlin its European “cool capital” reputation, one that to this day continues to attract arty (and party) types from all corners of the globe. Lots of them. Some stay for a long time, others short. Some forever. Some leave and come back, repeatedly so. Either way these creative immigrants don’t just ‘take’, they also contribute, leaving behind traces of their own lives and influences. The effect is viral and ‘infects’ both ways.

A fact not lost on Christian Vance. The “Australian electronic music industry veteran”, DJ and event producer has been living and working in Berlin for the last four years, the unsurpassed hub of electronic dance music in Europe. For longer he’s been doing his darndest to foster relationships between the Australian and German dance music communities. He says both camps have contributed mightily to each other’s music, tech, arts and business sectors.

He thinks it’s time this was recognised. Officially.

To that end Christian seized a rare opportunity. With the support of the Federal government’s annual Australia Now cultural initiative (this year taking place in Germany), Christian has not only attempted to drag electronic dance music ‘above ground’ and into the cultural ‘centre’, he’s also managed to make visible this decades-old, little-known, Australian-German cross-cultural relationship. And get it publicly acknowledged. With public money.

He created The Zeitgeist, a two-day showcase of Australian dance music in Berlin and celebration of German-Australian dance connections. He also put a big fat panel discussion called “Australian electronic dance music now” front and centre Opening Night. Nothing invisible about that.

Invited to speak were a range of Australian DJs and event producers, including veteran dance pioneers Simon Caldwell and Mike Callander; Brisbane-born DJ and soundtrack composer Claire Morgan and Berlin-based Australian DJ, Emma Sainsbury (“Eluize”). In his first time out (easy done!) Christian moderated. The audience was heartily invited into the conversation.

As Christian stated in his introduction (both with humour and gravitas), a serious discussion about where dance music sits within Australian arts culture wasn’t ‘usual’, more-oft dismissed as the meaningless, hedonistic pursuit of ‘the young’. Roger that: heaven forbid dance music, its practitioners and audience be perceived as a legitimate artistic, cultural and industrial force in its own right, cultivated over years of practice, inter-disciplinary and international relationship-building…

That – plus laying claim to a rich, vibrant cultural history of its own. The world as we know it might end… (It didn’t.)

It might take more than two days of The Zeitgeist to convince the folks ‘back home’ otherwise, nonetheless the event had plenty of happy, engaged Australian and German supporters. The conversation was intelligent, lively, specific but not ‘exclusive’. It was an inclusive, germane dialogue – a generous and interesting exercise in inquiry, listening and response.

Panelists shared observations made over long periods of working hard for little or no money (or recognition), having to do everything solo (Business! Tech! PR! Performance!). Also looking to mentors across the sea and jumping into the deep end of the pool in places like Berlin, where dance music is more respected and taken seriously as an art form.

Where it’s given a seat at the cultural table.

As both Emma and Claire iterated, performing and promoting in Berlin – often in world-renowned, seminal clubs such as Tresor or Berghain – means you have no choice but to ‘excel’. ‘It’s put up or shut up’ in front of audiences and promoters who expect the best. No room for slackers. (Someone also likened DJing at Berlin clubs to performing at the “Olympics”.) Watching and working with Berlin DJs on home soil also creates a similar ‘upscaling’ effect.

Leave it to a diplomat though… It was perhaps Sinje Steinmann, the programmer of Australia Now from the Australian Embassy in Berlin, who brought the best comment of the evening. Genuinely excited by the discussion, she compared the long history of Australian DJs working and honing their skills at the uber-clubs of Berlin, to that of the exodus of Australian classical musicians to the concert halls and music schools of Europe, a hundred years before. Undertaken to better themselves as artists. To cross-pollinate. The room suddenly went quiet under the weighty insight of the question. A line between the past and the present had just been drawn.

Had just made everything clear.

In that moment Australian electronic dance music was indeed elevated to ‘legitimate’, the parallel history on offer suggesting that dance music was as valued – and valuable – as classical. (Quite ironic too given that, commercially at least, the popularity of dance now surpasses that of classical music, struggling to survive by comparison.)

Christian looked pretty happy. ‘The experiment’ was a success – this night in Berlin anyway.

Let’s dance.

Circus Folk: How long have you been involved in electronic music? And what inspired you to dive in?

Christian Vance: Professionally almost two decades, however I’ve been collecting records since 1993 and the age of 14. My uncle, only twelve years my senior, had been studying in Switzerland in the late 80s and came back home raving about these cool new club sounds he had been hearing – and dancing to – in Europe.

The early 90s also saw some crossover House and Techno music in the charts; I was watching Rage on ABC at all sorts of hours to catch snippets of these new electronic dance sounds.

Independent and community radio was also a big factor for me as a young teenager in Melbourne: Liz Millar with her show on PBS and Kate Bathgate on RRR were great introductions, not only to new music, but to new sounds and foreign accents on air from visiting producers and DJs. Later triple j had Mix Up late on Saturday nights and stations like Kiss-FM were born. It was a window into another universe – what more inspiration does a teenager need right?!

CF: How would you describe your own particular “oeuvre” of electronic music? And who are your influences?

CV: Honestly, I’ve always cited the Underground Resistance EP “Belgian Resistance” from Detroit as one of the first records I ever purchased that blew my mind. This was different – obviously dance music with a repetitive groove, but wild and otherworldly. Powerful actually. It also played from the inside out with some crazy conceptual etchings. It was Mike Banks, Rob Hood and Jeff Mills all on one label.

So for me, Detroit Techno has always been a staple, and as a result of that, House music from Chicago and New York. This record drew a line for me, from Europe to America and back.

I could trace the historical, political and musical connections. Far away, obscure, hopeful. Basic Channel records from Berlin were closely-tied artistically and also shared a similar ethos and aesthetic.

It was music to think about and dream to while dancing – primal and futuristic at the same time. I hope, in some small way my “oeuvre” is part of this continuum. I would also have to say Derrick May was undoubtedly a mentor, with [other inspirations] many friends, producers, DJs and creative minds in Melbourne.

Panel chat: Christian with Emma Sainsbury (“Eluize”) Photo: Zoe Spawton (c) 2017

CF: Why have you devoted so much of your musical life to this genre – how did you find your way to it? And where does its power lie for you?

CV: Answering this particular question made me hesitate a little, [as] the real gut response to this is intensely personal. It was not only a coming-of-age experience to first dive into this music, but also coincided with a very devastating period of my teenage life, inextricably tied to grief, pain and triumph. And joy – yes – but an overwhelming sense of triumph. I had found a new language, something which many of us deeply into electronic music truly still feel even after all these years.

I’m a huge science fiction fan and there are aesthetic elements that quite obviously tie neatly into this particular way of experiencing music.

There is also freedom: to me House music has always exerted an energy of freedom – social freedoms, the good fight.

Techno music bridges that with a desire to contemplate the future and delves deeper into certain philosophies when you consider the more experimental, ambient and industrial offerings related to it.

Then there is celebration. This is music for ‘searching within’, exploring possibilities and to celebrate life with others. This is where the power lies: dance music that at times can be fun, intellectual, crazy, communal and also spiritual.

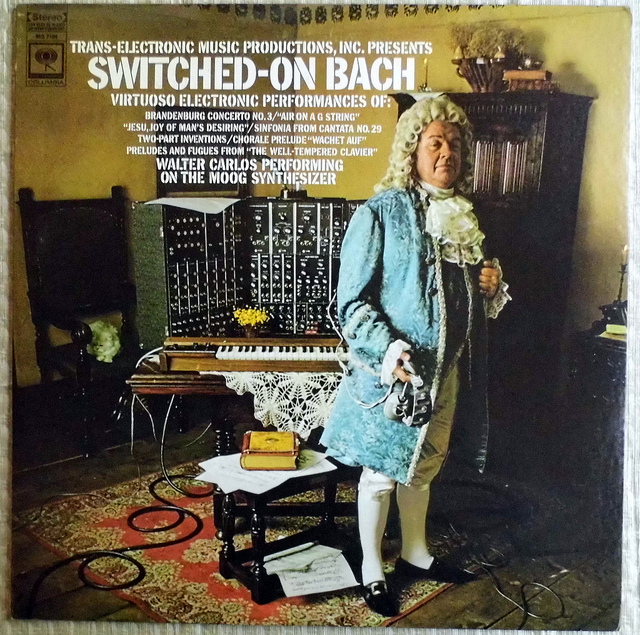

CF: I think – like so many born in the 60s! – the first electronic music I ever heard as a nipper was ‘Popcorn’ (Hot Butter version) and also ‘Switched on Bach’ by Wendy Carlos. I remember being shocked (it was so ‘alien’) and intrigued (it was so exciting), then totally falling in love with the sounds I heard in these recordings. You’re a late 70s baby: do you remember the first “electronic” artist you heard, and recording?

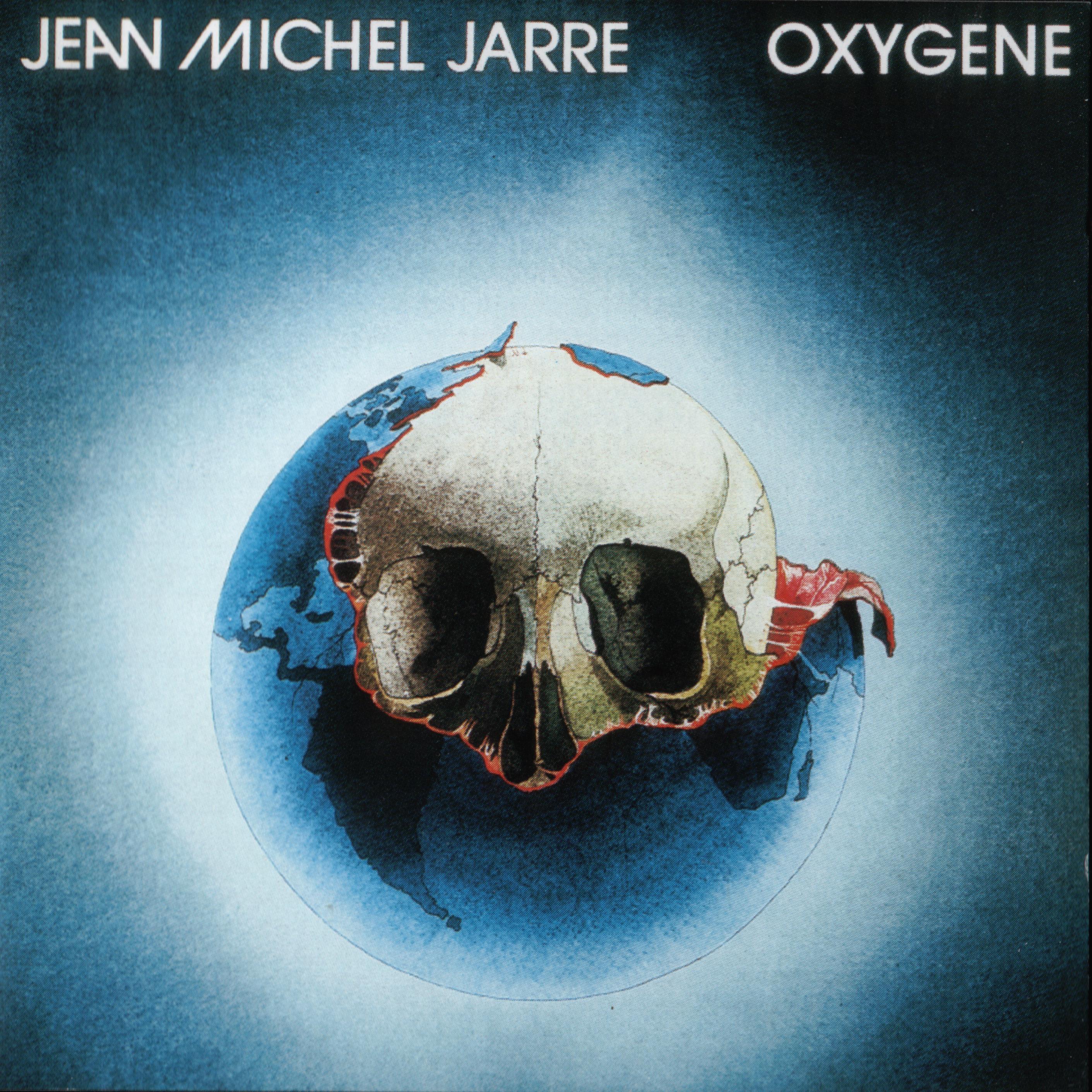

CV: The first ever electronic sounds I heard were probably on the radio in the early 80s: Eurythmics and ‘Sweet Dreams’, Jean-Michel Jarre and ‘Oxygene’. And in the late 70s even with Donna Summer with Giorgio Moroder, Vangelis, and the synth parts on Michael Jackson and David Bowie records. These are still pieces of music that gel with me even after severe radio overkill!

The most monumental memory though is the Boss Dr-55 drum machine my Dad used as an accompaniment to his electric guitar. It was quasi-programmable and the machine and its sounds intrigued me no end. I was playing around with that thing before I even started school! Music meets outer space in the comfort of your own home…

CF: Generally speaking, I find electronic music is such a diverse, cross-referential and inclusive type of music, with propelling people to get up and dance its universal ‘spine’. It’s far more organic, skillful and creative than people often give it credit for. So has the prejudice against electronic music – that it’s not “real” music, that it’s “synthetic” or somehow “illegitimate” – passed now? Or does the genre still face resistance from the ‘music mafia’ and other detractors?

Electronic music is very inclusive compared to many other types of music, both institutional and underground. To all its detractors – go jump in the lake! To create this music – for me anyway – you have to be part-musician, part-artist and part-engineer. It intersects many things that have come previously and begins new conversations around ‘what music is’ and ‘what it means’.

That “universal spine” you refer to is an interesting one. While the popularity of it is inextricably tied to dancing – this is how the culture has evolved and expanded – yet much of the first electronic music composed was much more experimental with no thought of engagement or entertainment.

And “synthetic” is a fallacy. We are human, organic, and we have created these machines and forged a new acoustic experience out of them. “Hyper-organic” perhaps? I feel that narrow judgement has definitely passed in much of Europe, perhaps Japan, but in many other places it can be a different story.

CF: From where do you come from in Australia and how long have you been in Berlin? How did you come to be here – and what do you love about living and working – in this city?

CV: I was born and raised in Melbourne and for the last five years I have lived in Berlin. There are actually a few reasons I came to be in the German capital. I was always fascinated by its relatively-recent 20th century history. It is the largest German speaking city and I’d already had an introduction to the language via my father (who had emigrated to Australia from Austria). So the language was therefore not completely foreign to me.

However the key reason was the fulfillment of a teenage desire to visit the famous/infamous clubs and record stores. I turned 18 in 1997 and can distinctly remember one gift that I received: a Tresor record bag – black with a bright red logo threaded on the outside. It lasted 15 years that bag! I already owned some of the records from the label and heard stories about the club. It was part of a dream.

That dream is still a major part of what I love about living and working in this city. I literally came for the history and the techno. The fact that they coexist at all is awe-inspiring regardless of the clichés. After visiting a couple of times a decade ago, feeling the energy of the different neighbourhoods – the liberal freedoms, playing gigs – it felt like a natural progression to move here.

CF: Berlin has such a history of supporting electronic music – and being somewhat of a “lab” for experimentation of this musical form. Why? Where has this come from?

CV: This is evident in much of German culture really – you just have to look at other fields and disciplines to see this. I respect that. Berlin, long before techno music, had been a melting pot of ideas. It is a big city with an intense history. The rise of the infamous clubs, Techno scene, Loveparade and so on, all evolved out of the time the wall came down. The story of electronic music, dancing, world events, communism, capitalism, squatters, late nights, cheap rents, cheap studios, transience, impermanence, partying – the list goes on! – all of these things were attractive reasons to visit, to stay, to try things out.

In this way Berlin didn’t ‘sell out’ too early or get stale. There are many forces at play and it could not have happened anywhere else like it did here.

CF: How did The Zeitgeist come about: what ‘impulse’ did it grow out of?

CV: Even before moving to Berlin I had questioned what kind of exchange existed between Australia and Berlin in regards to electronic dance music – and how it might be enhanced in terms of awareness within the cultural sphere. If it was important enough for many individuals to travel to Berlin ‘on a wing and a prayer’ – in some respects like TV or movie actors heading to Hollywood – then what kind of help or even awareness [of Australian artists] existed, if any, in an official sense?

There are so many young Australians in Berlin right now because of the music, compared to even 5 or 10 years ago. In this sense it really is a special time, one that I truly feel should be celebrated, discussed and put on record – literally! We are a long way from home!

This is a first for me to direct and curate an arts program or festival of this nature. But I have organised many music events over the past fifteen years, toured many artists from all over the world and programmed music for various labels.

The Zeitgeist combines that experience and knowledge with the goal to bring [electronic dance music] towards the cultural sphere and the so-called “real music” that is usually associated with anything official in the arts and so forth in Australia. It’s a valuable cultural commodity.

CF: Do you expect The Zeitgeist program to be well supported here in Berlin?

And why did you program a panel discussion into it? And what kinds of conversations are needed at this particular point in time, about electronic music – especially with this emphasis on Australia and Berlin?

CV: I hope it will be well supported. Of all the artists, bookers, DJs and promoters I have discussed this project with in Berlin – from every corner of the globe – the interest and response has been great so far. The panel discussion was conceived in order to have an official document and dialogue on record: “The Zeitgeist: where are we at now?” This is about exploring the past, current – and hopefully – future connections between Berlin and Australia within electronic music.

There are some important differences that are worthwhile discussing if we indeed value its cultural significance. I will leave that for the panel discussion itself, but by exploring the differences and similarities – then using that information in a practical, meaningful way – that is the goal of the panel.

The Zeitgeist panel: L-R, Simon Caldwell, Mike Callander, Christian Vance, Emma Sainsbury & Claire Morgan. Photo: Zoe Spawton (c) 2017

CF: Including yourself there are 10 Australian DJs included in The Zeitgeist program: how did you go about selecting the artists involved? What is it you appreciate about their individual work and/or contribution to electronic music?

CV: Many and varied! It was a selection process not only about individuals but creating a representative mix. One artist will be performing for the first time in Berlin but has released music on a Berlin label. One DJ first played Berlin at the original Tresor in 1998. Some run events, labels, play live, engage artists from Berlin for their own record label, work within education of electronic music… Some live here, some are on tour and so on.

I appreciate every single one of them for their contribution to the advancement of Australian electronic music culture. They are all an important part of that story right now.

CF: “Celebrating and exploring the connections of electronic music between Australia and Berlin” is the by-line for Zeitgeist: what are these connections exactly? Has there been a healthy exchange of artists and collaborations between both?

CV: I think electronic music is a great example of the connection between the two countries right now. On any weekend there will be Australian DJs playing in Berlin in a respected club. There are always artists and DJs touring Australia from Germany, artists from Australia that visit, tour and play in Berlin, and those who are living and working professionally in the city. These are where most of the connections lie – there are myriad as a result of this. Events, collaborations, labels, records, parties, tours all come about because of these relationships.

The ‘snapshot’ is that now, more than ever, this exchange has reached a new intensity with more and more Australians moving to or performing in Berlin. There’s not really that much on ‘official record’ about those past connections or even the current ones.

If young creatives flock here then hopefully that’s all the motivation needed to ‘inquire a little further’ – to dig a little deeper. It is incredible that many make this move to explore their creative potential.

CF: The Zeitgeist festival in Berlin is being supported by the Australian government, through its annual cultural initiative ‘Australia Now’: how does that make you feel? And does it mean electronic dance music is perhaps moving away from its oft-referred-to “niche” subcultural status, and being recognised for the cultural ‘force of nature’ that it is?

CV: It feels terrific to be honest! I also feel it is very unique but very representative of Australia right now in Berlin. It is quite common to hear an Australian voice at a cafe and at the club – and not just during the summer.

Berlin is the world capital for this music and culture right now. Perhaps by drawing a line from here to Australia and back it can set the wheels in motion to bring that subcultural status closer to the traditionally recognised arts back home.

Berghain, here in Berlin for example [one of Berlin’s most famous and seminal dance clubs], has collaborated with the ballet, the Staatsballett Berlin. They also have a special tax exemption because the venue is considered part of “high culture”. This sets a great example for other regions and institutions. It is not just a cultural “force of nature” in Berlin, but one that is becoming increasingly global.

[Zeitgeist] is perhaps a small step, using the example of Berlin, to identify electronic music and the people involved, as a genuine, legitimate part of culture. The Australia Now 2017 program provided that opportunity and it was a great honour to have the proposal for The Zeitgeist and ABEC [Australia Berlin Electronic Connections, the entity presenting the inaugural Zeitgeist program] supported in this way.

CF: Do you feel that ‘cross-cultural’ events such as this are important to a country such as Australia?

CV: 100% yes. Because we learn through the exchange of not only new ideas, but of shared experiences. It still takes one whole day in a plane to fly back and forth [between Australia and Berlin.] The internet has changed many things; but that of the ‘physical’ experience – sound and conversation in particular spaces – that will always be fundamental.

CF: What do you hope comes out of The Zeitgeist?

CV: I hope we establish new connections and respect the existing ones. And I hope it’s a stepping stone towards uniting electronic music culture with more-established and recognised art and culture, within our institutions.

* * *

Many thanks to Christian for the interview and invitation to attend The Zeitgeist; to the panelists and guests for the photos; Sinje Steinmann, Rachael Vance, and Zoe Spawton for sharing her images with me!

* * *

- Interview: Christian Vance

- Words, edit + photos (where credited): Megan Spencer

- Visit: The Zeitgeist website and on Facebook

- Listen: to Christian’s music on Soundcloud

- Follow: Christian’s tour dates

- View my Zeitgest photo gallery on SmugMug

- Listen: to the music of Simon Caldwell, Mike Callander, Trinity, Dave Stuart, Claire Morgan and Eluize.

- View: Zoe Spawton Photography

- Read: more about Australia Now

- Listen to my Mad Love feature on Radio National (another story from Berlin in the Australia Now program.)