I’ve always been fond of ‘goo’.

It’s the name of my favorite Sonic Youth album. It’s one of my favorite words, caught somewhere between “coo” and “gum”.

And ‘goo’ has always been one of my favorite things to eat, especially if it’s coloured pastel pink. Growing up in the 70s I consumed my fair share, especially ‘Junket‘, one of my mother’s specialties.

It would arrive as ‘sweets’ at dinner parties, often on the heels of pineapple ham steaks or chicken chow mein. It was the gelatinous, wobbly version of musk sticks, fridge-set, in tall curvy glasses on stems. A sugar coma in the making, us kids couldn’t get enough of it.

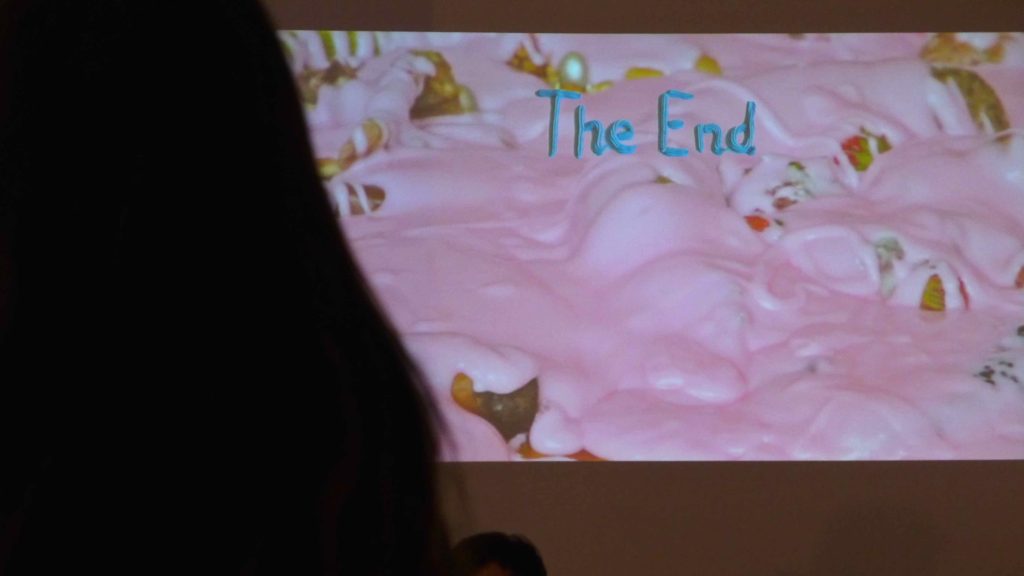

All these years later and on the other side of the world, Junket oozed its way back into my memory at a recent “work-in-progress” screening at the Australia Council’s residential artist studio in Berlin. It was for short video The End Of The Sausage Fest, made by Melbourne’s gleefully subversive art+craft collective, Hotham Street Ladies, with two members, Australian artists Lyndal Walker and Caroline Price, in situ.

Projected onto a wall of “international culture centre” Künstlerhaus Bethanien (Lyndal’s current base as a recipient of its artist-in-residency program), the film was an apt offering to the centre’s annual “open studio” menu. Made after a humid, heady afternoon at Thai Park (a local open-air foodie paradise), the Ladies’ luminescent symphony of goo certainly did “playfully explore patriarchy, decadence and male privilege.”

I was among the silhouetted group entranced by this silent visual loop, watching mounds of sticky pink icing unceremoniously plop onto of all manner of oral indulgence, the remnants of which can only be described as a disgracefully decadent dinner party. The phallus of a dead cigar included, it was as if Peter Greenaway’s film The Cook, The Thief, His Wife and Her Lover had been stuck in a blender, covered in pink icing and served up for our rapidly-diminishing attentions spans. It was enough to make you reach for a doggy bag or laugh-out-loud in gallows humour.

Eat The Rich. Repeat.

‘The End Of The Sausage Fest’ video by The Hotham Street Ladies. Photo: Megan Spencer (c) 2016

Hotham Street Ladies in Berlin: Caroline Price & Lyndal Walker, Künstlerhaus Bethanien. Photo: Megan Spencer (c) 2016.

Clearly a fan of goo and its power to revolt, engage and entertain, Lyndal Walker is a photo-based artist with a penchant for “disruption”. As it says on the KB website, Lyndal’s work “emerges out of an ambivalent relationship to consumer culture. She is fascinated by our voraciousness but also finds it deeply morbid. While she has often used photography in her work, she is interested in disrupting the role of the photographer. She has extended her conceptual concerns to destabilise the photographic object by printing her images on silk scarves or mounting them on mirrors.”

After a long-time flirtation with Berlin – and spurred on by a chance meeting with a member of indie-pop royalty – Lyndal finally arrived to live in April 2015. She’s found the right city in which to make her art, one renowned for questioning norms and criticizing the ‘status quo’. And, embracing those who do.

Lyndal is interested in disturbing standards – especially entrenched ways of looking at the world. An artist with a long list of credits (her first solo show was in 1994), she’s working both on individual projects and collaborations during her 12-month Berlin residency, including one with painter Tony Clark, about Rowland S. Howard, the late Australian post-punk guitarist, himself a former Berliner. A solo exhibition in April 2017 is also on the cards as part of her residency.

The enormous Licht Fabrik building in which Lyndal’s studio is housed is a former light factory, re-purposed to support a myriad of progressive artists, gallery spaces and start-ups. The labyrinthine structure goes on for days.

It’s a spacious, historic and fertile place for making art, conversation and more, as I discovered when we met for Circus Folk.

Lyndal Walker in her Berlin studio. Photo: Megan Spencer (c) 2016

Circus Folk: I believe it was a long time ambition to live and work in Berlin: what was your trajectory, and motivation to move here?

Lyndal Walker: I first came to Berlin in 1996, as part of a backpacking trip when I was 22. A good friend from Melbourne (now a gallerist here in Berlin) had moved here and I stayed with him in the then-very rough Neukölln.

Honestly I wonder why I loved it so much then: it was the middle of one of the coldest winters for decades – minus 22 degrees – and Berlin was very different. It was very poor and not full of the bourgeois delights of bars, cafes and galleries that it is now.

I really would have loved to have moved then, but it wasn’t easy to get visas and learning a new language was a hurdle I wasn’t willing to jump at that time. I kept visiting. In 2014 I was here and I just had this thought going around my head, “why don’t I move to Berlin?”

I don’t usually tell this story because one of the nice things about Berlin is [that] celebrity culture isn’t really respected here. But here goes: by chance I met Michael Stipe at an exhibition opening. We got chatting and I said I was having this thought about moving to Berlin.

He said “how are your parents?” I told him my father was dead and my mother in good health. He said “well you must move to Berlin now,” and I knew he was totally right. It was a very well placed question.

CF: Has Berlin met your “expectations” so far? As a place for your practice and a culture in which to live?

LW: I couldn’t say what my expectations were, but what I can say is that I feel very stimulated here and I realised, once I’d decided to leave Melbourne, that I really hadn’t felt very stimulated there for some years.

I feel Berlin offers me lots of new information and life challenges as well as art to see and artists to meet, so as a culture and place for my practice, it’s great. It’s a very dynamic place but unlike other cultural capitals like London or New York, it’s not very consumerist.

It’s calm and cheap, but really exciting.

Lyndal Walker and ‘The Artist’s Model’. Photo: Megan Spencer (c) 2016

CF: Sometimes people (especially ‘creative folk’) have romantic ideas about moving to Berlin: that it’s all ‘beer and skittles’, a 100% party town with arty types on every corner doing whatever they like with very little. What has the experience – and transition – been like so far for you?

LW: Having spent quite a lot of time here before, I had a pretty good idea [about] what living here would be like. I had dreaded the winter and it’s not easy but actually I like the way Berlin is a completely different city across the seasons.

As for “beer and skittles” and “creative people on every corner”, I’m glad it’s not like that. The jugglers are one of my least favourite aspects of the city and thankfully they are not around in winter!

It’s a great city for me. It’s very stimulating and a lot of the things I’m particularly interested in are really fundamental here. For example there is lots of experimentation with different ways for living, whether it be artist-led projects, communal living or polyamory. People really play with gender and its representation a lot here.

I’m not really sure what opportunities will come here. I’m still in the early days of establishing my practice in Europe. For one thing, being in the centre of Europe makes having an exhibition in Stockholm – as I did last year – a lot easier than if I was in Australia.

Berlin is just a great city to be an artist in very practical ways, because there are so many of us here. So when you front up to the glass cutters for example, they’re not surprised you’re an artist and they are happy to do things differently, or know that it’s important for things to be well finished. Even going to the accountant is a whole lot easier. Apparently there are even therapists here who only work with artists.

CF: For how long have you been an artist? And do you remember the moment when you realised – or decided – that this is what you wanted to do?

LW: I’m one of those rare people who always wanted to be an artist although in reality I didn’t know what that meant when I was a kid, because I never knew other artists until I went to art school.

Of course I was encouraged to do something more practical, and actually I had a lucky break when the then-Premier of Victoria, Jeff Kennett, sacked so many teachers in the 90s, because I’d told my parents I would do teaching after my fine art degree and become a teacher.

By the time I graduated that was as impractical as being an artist!

Work by The Hotham Street Ladies. Photo: Megan Spencer (c) 2016

Lyndal Walker. Photo: Megan Spencer (c) 2016.

CF: Last July you received your first grant from the Australia Council, which supports a unique artist residency in Berlin at Künstlerhaus Bethanien, a cultural institution “whose goal is to further contemporary art and contemporary artists”.

How difficult was it to get into, and what does it mean to you to receive this kind of support at this point in your career: is it encouraging?

LW: I first applied for the Künstlerhaus Bethanien studio in 1996. And while I haven’t applied every year, I’ve probably applied about six or seven times, and well, it’s been twenty years in the making.

There are nineteen other artists in the building from countries including Korea, Ethiopia, Iceland, Canada and Cyprus, so it is genuinely international.

Yes of course it’s encouraging. Most artists struggle with a sense of self-worth and wonder what the point of their practice is, particularly when it cost us so much financially and personally. I wasn’t getting very many opportunities in Australia in the last few years so this is a very positive development for me.

To be supported for a year in a beautiful studio surrounded by other artists is great in so many ways.

Artist Lyndal Walker with a work from her ‘Silk Cut’ series. Photo: Megan Spencer (c) 2016

CF: As an artist you have developed a number of interests and ‘lines of inquiry’ in your work, and moved from painting to photography, combining both within your practice and image making. Could you please give us an idea as to where you started and where you’ve ended up in terms of themes you’ve explored? Especially with regard to your more recent projects?

LW: When I started exhibiting I was very interested in fashion and I was quite obsessed with the passing of time. I’ve also always been interested in the politics of representation, particularly as it relates to gender roles. My interests in fashion have moved towards a particular interest in the process of dressing and states of undress.

I’ve always been interested in the way women bond over clothing. It is both a way of expressing ourselves and a subject to communicate about. As my practice has developed, I’ve become more interested in the metaphorical aspects of dress and undress, so issues such as exposure, shame and vulnerability are of increasing interest to me.

I’m also really interested in materials related to fashion, like silk and mirrors. In ‘Modern Romance’ and ‘Silk Cut’, my interests in fashion and sexual imagery intersect. In ‘Silk Cut‘ I’ve printed images of men (images of erect penises) on silk scarves. It’s the first time I’ve made a wearable object.

My concern with representation has most recently manifested in my being present in my images, taking the photos of young men in the series ‘The Artist’s Model‘. I’ve also become more interested in contemporary images like those found in sexting and porn.

CF: There is an unabashed voyeuristic aspect to your work, in as much as you’re interested in the process of looking, and making that quite overt: from the subjects of your work looking directly at the viewer and you placing yourself in your work, to looking at (and making photos of) your subjects. Looking is something we do prolifically and often without much conscious thought or attention: so what is it about “looking” and the act of it that attracts you as an artist? And what are you trying to say to us about it?

LW: Interesting question! I am really interested in questioning images and drawing attention to the fact that you are looking at a picture, and that its relationship to reality is not entirely smooth. Using frames, collage and including myself in my images, I hope to inspire people to ask questions about the images they see around them.

I’m also interested in truth and fiction and how we distinguish between them. I like storytelling, particularly when it challenges the nature of reality. I’m always been interested in communication, and ‘looking’ and ‘seeing’ are forms of communication.

I often wonder about the value of art and how we might make any difference to the world with it. We are surrounded by images, and from early in my career I was interested in advertising. Although my work addresses that in less literal ways now, I think it’s important that we are constantly questioning the images which sell us not only products, but expectations about our lives and bodies. The nature of visual art is that we are looking at it, so I think art is still a great place to explore the nature of beauty and if it is important.

Recently I’ve been thinking what a privilege it is for straight men to constantly see images of beautiful women often without much on. They have their sexuality and desire regularly reaffirmed and stimulated. And this is a way in which ‘looking’ and ‘seeing’ are part of power relations in our lives.

CF: There is an undertone of ‘profanity’ (explicit nudity, sexuality) that has also popped up in your work too – from the “penis scarves” to images in the ‘Modern Romance’ series. When did you start to bring that into your work? And what ideas are you exploring in this arena?

LW: The profanity is relatively new, since a show I did in Melbourne in 2013. I’ve always rather delighted in the chasteness of my previous images of people in their underwear. But even with ‘Silk Cut’, the larger than life erect penis is usually hidden within the soft folds of the silk, so it’s not so explicit either.

Those images are inspired by sexting and as such continue my interest in the role of the photograph in our lives and to our identities. I’ve always been interested in identity so an aspect of that work is to wonder, if you receive an image of a penis, does it belong to the person who sent it? And how important is a man’s penis to his identity?

I’m also interested in the fact that men’s bodies are now being fragmented through imagery, in the same way that women’s have always been. As with most of my work, it’s an experiment: What is it for a woman to wear an image of a penis around her neck?

I have become more interested in porn and kink since I’ve been living in Berlin. In Australia I didn’t really think of porn as something that might inform my work, but in Berlin sexuality is taken seriously as an intellectual pursuit. Also there are things like the Berlin Porn Film Festival, which shows challenging, non-exploitative works so I’m more engaged with ‘profanity’ here. Kink is interesting to me because of the way it playfully explores power dynamics.

People are very open about their bodies here. You often see nude people in the park. I need to be more prepared next spring with good underwear because if it’s a sunny day, people will get down to their knickers at a picnic! There’s also such a massive kink scene so people are speaking very openly about their sexual desires.

I’m not sure how literally my work will reflect these interests, but for now they are inspiring lots of interesting thought.

In black & white: Lyndal Walker. Photo: Megan Spencer (c) 2016.

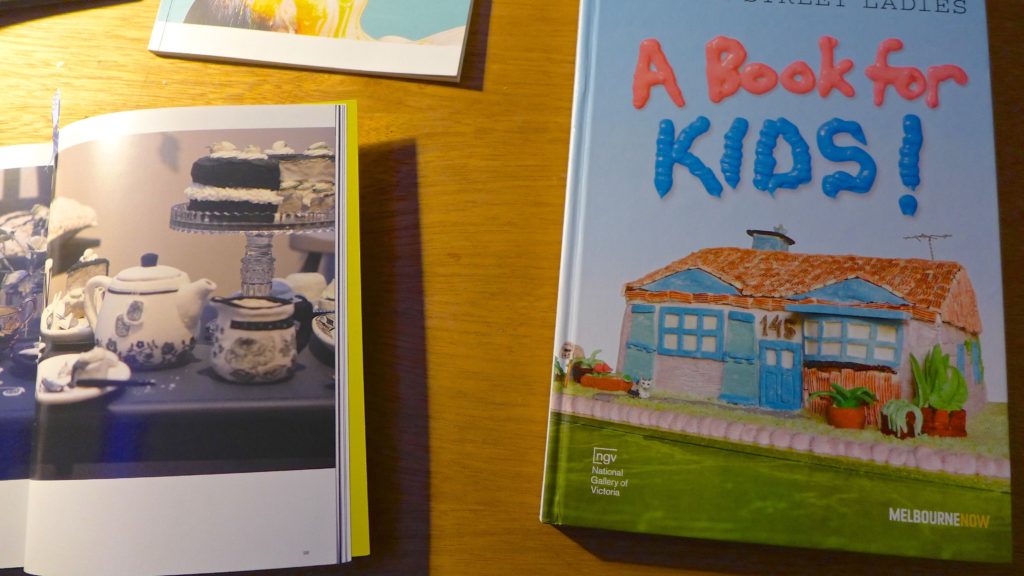

CF: The Hotham Street Ladies have become a bit of an institution in Melbourne. For those who may not be familiar, could you please provide a ‘snapshot’ of the collective? And more of an insight into the new video project The End Of The Sausage Fest that was made at your Berlin studio?

LW: There are five Hotham Street Ladies and we all met living in a share household in Collingwood, Melbourne. We started by making a couple of recipe books for our friends and then we made some cakes that we submitted to the Royal Melbourne Show. Then some street art.

Then things got a bit more serious with a permanent public work on Hoddle Street in Melbourne and various installations, including a major work as part of ‘Melbourne Now‘ at the National Gallery of Victoria in 2013.

These days, Caroline Price and I work together in Europe, and Cassandra Chilton, Molly O’Shaughnessy and Sarah Parkes work in Melbourne. When I was in Melbourne earlier in 2016, we brainstormed a work that the Melbourne crew made and which is currently on at The Johnston Collection in Melbourne. And in a rare moment all of us were together to install a work at Shepparton Art Museum in February.

The End of The Sausage Fest is a video that Caroline Price and I made in my Australia Council studio in July ’16. We set up a scene which we thought of as a kind of ‘power dinner’ but with a lot of stuff that was moldy and rotting. We had been talking with frustration about a lot of self-serving male leaders: we were thinking of some of the really rotting and rotten patriarchal values which are now being exposed and challenged. The video involves a flood of pink icing and glitter that subsumes all the rotten old leftovers.

CF: Was it a fun project?

LW: Although the last thing any of us want to do is eat icing, I think the nature of icing and cake is that it is fun and celebratory. Sometimes I feel when we’re developing ideas that we are on a sort of ‘sugar high’. What’s not to like about thinking up food metaphors for cunnilingus or making cigarette butts out of icing?!

As a solo artist, working in a group is very liberating. You can really delight in one another’s work, and the sort of doubts I struggle with in my solo practice are much more quickly resolved in a group. I think one of the things that’s great about HSL is that it does reflect the satisfaction a lot of women find in making things, and the fun and support you get from working with a community of other women.

CF: Speaking of collaborations, you’re in a long-term and long distance one with painter Tony Clark. It has tendrils in both Melbourne and Berlin, courtesy of the late Australian musician, Rowland S. Howard…

LW: I saw Rowland Howard’s final gig in 2009 and he had this incredible quality which made me really want to photograph him. He was very frail, but kind of boyish at the same time, [and] in a way that was similar to the young men I’d photographed in ‘Stay Young’.

I mentioned this to Tony who said he wanted to paint Rowland’s portrait. Tony was an old friend of Rowland’s and arranged for us to make our portraits together but Rowland died before we could. I was devastated: I was a massive Birthday Party fan when I was a teen and always felt sort of ripped off that I hadn’t seen them because I was too young. So missing taking the photo echoed that experience.

Tony and I decided to do the work anyway but instead of a photographic portrait, I’ve written about Rowland and my own fandom and the nature of portraiture and the passing of time, while Tony has painted Rowland. It will be a book when we finalise it.

CF: As an artist, as it been a tough road to get to this point? What keeps you going?

LW: Sometimes I wonder: these days I feel very strongly that I just am an artist. That I don’t really have a choice. But I wasn’t always so romantic. There’s been two stages in my practice when I very seriously considered quitting and I think that is a really important process that I would encourage all artists to go through. I’ve come back from those periods with more resolve and a clearer sense of what I want to do and why.

As for it being a tough road, I’ve been fortunate to have had some great opportunities, but they don’t always lead to other opportunities. So there’s not much sense of your career ‘growing’ in the same way most people’s careers do with more status and more money. Of course it’s such a privilege to be able to spend time following your obsessions and developing something that is so personal. On the other hand, you have to constantly motivate yourself and face a lot of rejection. It’s good to be in Europe where being an artist is respected.

About ten years ago I had a really hard look at my practice and career and asked myself what I was getting from it and what I wanted from it. I think the community and friendships around my art practice are the best things. I’ve also had the opportunity to travel with my practice, and as travel has always been important to me, I decided to focus on getting more of those opportunities.

So those are some of the things that keep me going, friendship and travel.

CF: As a “Wahlberliner” (Berliner by choice), do you have an experience of Berlin that sums up why you enjoy being here?

LW: Recently I’ve noticed how easy it is to be alone here. I always spend a lot of time alone, and in a lot of places that makes you a bit of a pariah – people feel sorry for you or think you need to be talked to. Here, there are always lots of people alone: smoking a joint by the canal, reading a book in a café, eating a nice meal in a restaurant… And your privacy is totally respected and there aren’t needy people trying to engage you in conversation and distract you from your thoughts or books.

I think I’d really miss that respect for solitude that Berlin offers.

With many thanks to Lyndal Walker.

Fin: ‘The End Of The Sausage Fest’ by The Hotham Street Ladies. Photo: Megan Spencer (c) 2016

- Interview: Lyndal Walker

- Words, photos + edit: Megan Spencer

- View: Lyndal Walker’s website

- Visit: The Hotham Street Ladies

- Read: Lyndal’s writing

- More about: Künstlerhaus Bethanien

- Recipe: watch how to make Junket

- Listen: to Goo.

Tagged: art, berlin, künstlerhaus benthanien, lyndal walker, photography